Beyond Zoroaster: Unmasking the True Zarathushtra and His Impact on History

Zarathushtra’s Revolution: How One Prophet’s Vision Shaped Ancient Persia and Beyond

The Undying Flame: Exploring the Core Tenets of Zoroastrianism and Zarathushtra’s Legacy Today

Shrouded in the mists of time, Zarathushtra emerges not just as a religious figure but as a revolutionary thinker who dared to challenge the established order. His teachings, often simplified as merely promoting monotheism, weave a complex tapestry of dualism, ethical living, and the eternal battle between good and evil. The echoes of his Gathas resonate even today, influencing major world religions and continuing to inspire spiritual seekers across millennia. From the flames of ancient Persia to the diaspora communities of the modern world, the legacy of Zarathushtra continues to offer a timeless message of hope, ethical conduct, and the pursuit of truth.

I. Unveiling Zarathushtra: The Man and the Myth

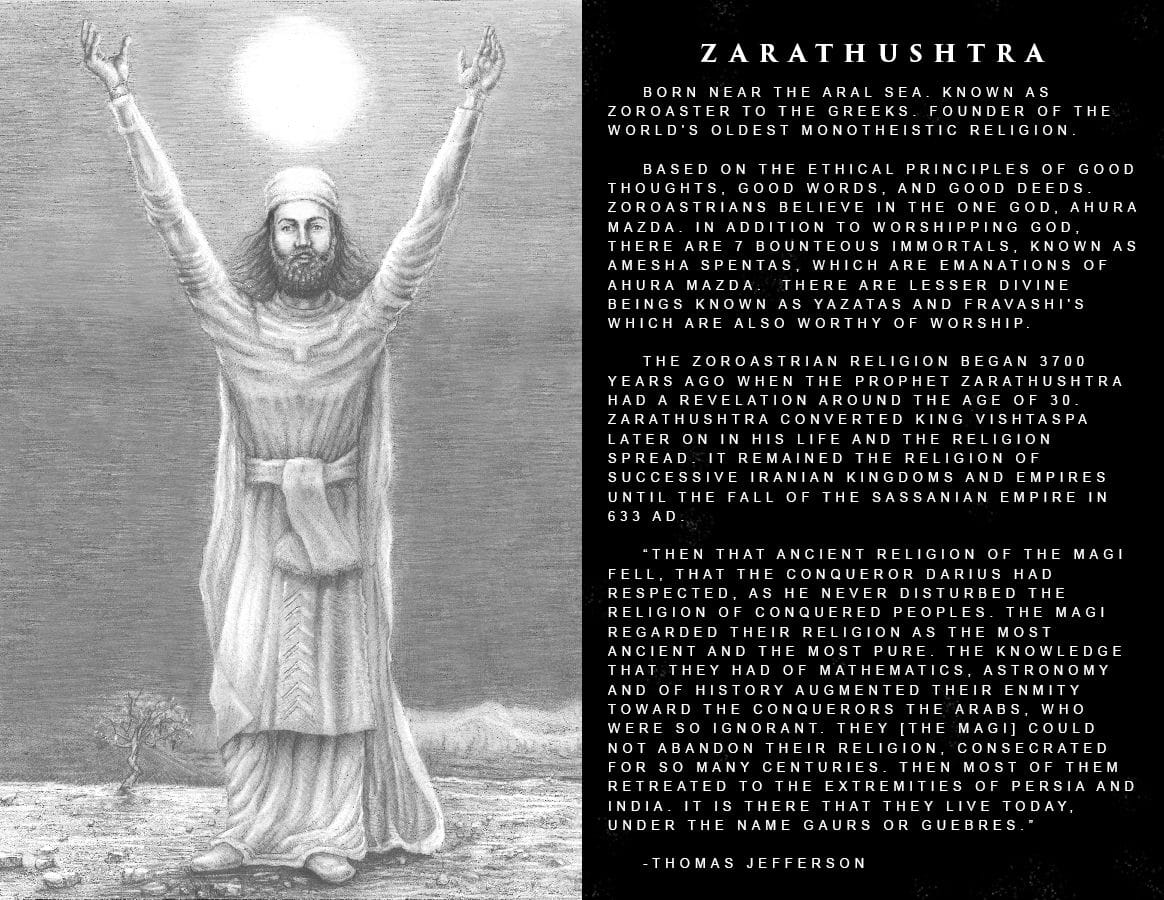

The life of Zarathushtra, the prophet who ignited the flame of Zoroastrianism, is a blend of historical mystery and enduring legend. While his exact dates remain uncertain, scholars generally place him between 1700 and 500 BCE in ancient Persia, a land steeped in tradition and ripe for change. The challenge lies in separating the historical figure from the layers of mythology that have accrued over the centuries, a task that continues to fascinate and frustrate historians today.

Even his name reflects this intriguing complexity. While commonly known as Zoroaster in the West, this is a Hellenized form of his original name, Zarathushtra, a name that echoes with linguistic significance, potentially meaning “possessing old camels” or “golden light.” This blending of the practical and the profound hints at the nature of the man himself, a figure rooted in the realities of his time yet driven by a vision that transcended earthly concerns.

Details about Zarathushtra’s early life are scarce, gleaned from fragments of later Zoroastrian tradition and scholarly speculation. He likely belonged to the Spitama clan and may have served as a priest in his early years, immersed in the polytheistic beliefs of his people. Yet, a restless spirit and a thirst for truth seemed to have stirred within him, leading him to question the established order and embark on a spiritual quest for meaning. Tradition holds that he received his pivotal revelation around the age of 30, a profound encounter with Ahura Mazda, the supreme God who would become central to his teachings.

II. The Pillars of Zarathushtra’s Teachings

At the heart of Zarathushtra’s revolution was a radical departure from the polytheistic norms of his era. He proclaimed the existence of Ahura Mazda, the uncreated God, a being of pure wisdom, righteousness, and truth, fundamentally different from the deities of the old ways. This concept of one God, a supreme and wholly good creator, was a seismic shift in the religious landscape of ancient Persia, paving the way for the development of monotheistic ideas that would shape world religions for centuries to come.

Yet, Zarathushtra’s vision extended beyond simply proclaiming one God. He envisioned a universe locked in a cosmic struggle, a grand battle between the forces of good and evil, order and chaos. Ahura Mazda, the embodiment of all that is right and just, is eternally opposed by Angra Mainyu (Ahriman), the destructive spirit representing darkness and lies. This dualistic view of existence formed a core tenet of Zarathushtra’s teachings, emphasizing the moral weight of every action, every thought, every word. Humans were not mere bystanders in this cosmic drama but active participants, tasked with aligning themselves with Ahura Mazda and contributing to the ultimate triumph of good.

To guide humanity through this struggle, Zarathushtra spoke of the Amesha Spentas, the “Bounteous Immortals,” seven divine emanations of Ahura Mazda, each representing a core aspect of creation and a guiding virtue:

– Vohu Manah: Good Mind

– Asha Vahishta: Best Truth (Righteousness)

– Kshathra Vairya: Desirable Dominion (Just Rule)

– Spenta Armaiti: Holy Devotion (Loving Piety)

– Haurvatat: Wholeness (Perfection)

– Ameretat: Immortality

These divine beings served as intermediaries between the supreme God and humanity, embodying the qualities needed to live a righteous life and uphold cosmic order.

Crucially, Zarathushtra emphasized that the battle between good and evil was not merely an abstract cosmic event but played out within the heart of every individual. He laid out a clear path for ethical living, a threefold path known as Asha, centered on aligning oneself with truth and righteousness through:

- Humata: Good Thoughts: Cultivating a mind focused on wisdom, honesty, and purity.

- Huxta: Good Words: Speaking with truth, kindness, and integrity, using language to uplift and heal rather than to harm.

- Huvarshta: Good Deeds: Acting with justice, compassion, and generosity, striving to make the world a better place through active participation in good.

This emphasis on ethical conduct, on personal responsibility for one’s thoughts, words, and actions, formed a cornerstone of Zoroastrianism, shaping its moral code and influencing ethical philosophies for millennia to come.

III. The Gathas: The Voice of Zarathushtra

While the life of Zarathushtra is veiled in the mists of time, his spirit speaks most directly through the Gathas, a collection of 17 sacred hymns enshrined within the larger body of Zoroastrian scripture, the Avesta. Composed in an ancient form of Avestan, a language closely related to Vedic Sanskrit, these hymns are believed to be the closest we have to the actual words of the prophet, raw and powerful expressions of his spiritual experiences and pronouncements.

The Gathas are not mere theological treatises; they are deeply personal poems, imbued with a sense of immediacy and emotional resonance. Within their verses, we encounter Zarathushtra wrestling with profound questions, communing with Ahura Mazda, railing against the forces of falsehood, and calling his followers to a life aligned with truth and righteousness.

Key themes echo throughout the Gathas, offering glimpses into the core of Zarathushtra’s revelations:

- The Nature of Ahura Mazda: The hymns paint a picture of a God who is not distant or indifferent but actively engaged in creation, a God who hears prayers, responds to devotion, and seeks to guide humanity towards wisdom and righteousness.

- The Choice Between Good and Evil: The Gathas emphasize the constant tension between the opposing forces of Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu, highlighting the individual’s responsibility to choose the path of Asha, of aligning oneself with truth and goodness.

- The Importance of Ethical Living: The hymns stress the practical implications of Zarathushtra’s teachings, emphasizing the need to translate faith into action, to embody the principles of Humata, Huxta, and Huvarshta in daily life.

- The Promise of a Future Existence: The Gathas offer glimpses of a life beyond this earthly realm, hinting at a final judgment, the triumph of good over evil, and the rewards that await those who have lived righteously.

Deciphering the Gathas presents unique challenges for scholars due to their archaic language and poetic symbolism. New interpretations continue to emerge as scholars delve deeper into the nuances of the text, ensuring that Zarathushtra’s message remains dynamic and relevant to each generation.

IV. The Enduring Legacy of Zarathushtra

Zarathushtra’s influence extends far beyond the annals of ancient history. His teachings, initially embraced by a small group of followers, would blossom into a major world religion, shaping the spiritual and cultural landscape of Persia for centuries. Zoroastrianism, as it came to be known, rose to prominence during the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550–330 BCE), becoming the official religion and deeply influencing Persian art, architecture, governance, and social customs. The grandeur of Persepolis, with its majestic palaces and intricate reliefs, stands as a testament to the cultural impact of Zoroastrianism at its zenith.

The influence of Zarathushtra’s ideas, however, transcends the boundaries of any single religion or culture. Scholars have long recognized the potential impact of Zoroastrianism on the development of major Abrahamic faiths—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. While the exact nature and extent of this influence remain subjects of ongoing scholarly debate, striking parallels exist in key areas:

- Monotheism: The concept of a single, supreme God, central to Zoroastrianism, finds resonance in the Abrahamic traditions, suggesting a possible line of influence.

- Angels and Demons: The Zoroastrian concept of a cosmic struggle between good and evil, embodied in the forces of Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu, finds echoes in the angelic and demonic hierarchies present in later faiths.

- Heaven and Hell: The Zoroastrian belief in a final judgment and an afterlife where the righteous are rewarded and the wicked punished prefigures similar concepts in Abrahamic eschatology.

- The Messiah: The Zoroastrian idea of a future savior figure, a Saoshyant who will usher in a final era of peace and righteousness, bears resemblance to messianic prophecies found in Judaism and later adopted by Christianity and Islam.

While these parallels do not necessarily prove direct borrowing, they highlight the profound influence of Zoroastrian concepts on the development of Western religious thought.

Despite facing persecution and decline following the Arab conquest of Persia in the 7th century CE, Zoroastrianism has shown remarkable resilience. Today, Zoroastrian communities, though smaller in number, continue to thrive in parts of India, Iran, and the diaspora, keeping the flame of Zarathushtra’s teachings alive. These communities, often referred to as Parsis in India, have played significant roles in their adopted countries, known for their ethical values, entrepreneurial spirit, and contributions to philanthropy and social justice.

The story of Zarathushtra is a testament to the enduring power of ideas. His message, transcending time and cultural boundaries, continues to resonate with those seeking meaning in a complex world. His emphasis on ethical living, the pursuit of truth, and the individual’s role in the battle between good and evil offers timeless wisdom, relevant today as it was millennia ago in ancient Persia. As we delve deeper into the legacy of this enigmatic prophet, we uncover not just a historical figure but a mirror reflecting our own capacity for spiritual striving, ethical reflection, and the pursuit of a more just and compassionate world.

V. Beyond Monotheism: Exploring the Nuances of Zarathushtra’s Divinity

While often categorized as a prophet of monotheism, Zarathushtra’s conception of the divine reveals a layer of complexity that defies simple categorization. The relationship between Ahura Mazda, the supreme God, and the Amesha Spentas, the Bounteous Immortals, raises fascinating questions about the nature of divinity in Zoroastrianism.

Some scholars interpret this relationship as suggestive of qualified monism, where the Amesha Spentas are seen as emanations or aspects of Ahura Mazda himself, representing different facets of his divine being. This perspective emphasizes the unity of the divine while acknowledging the multifaceted nature of the divine essence. Others lean towards a more nuanced understanding of monotheism, where Ahura Mazda reigns supreme, yet chooses to manifest his will and power through these divine emanations.

This debate highlights the depth and philosophical richness embedded within Zoroastrian theology. It prompts us to consider whether strict monotheism, as understood in later Western religious traditions, fully captures the essence of Zarathushtra’s vision. Exploring these ambiguities provides fertile ground for theological inquiry and reveals the sophisticated cosmology underlying his teachings.

VI. Zarathushtra as Proto-Philosopher

Beyond his religious contributions, Zarathushtra’s ideas offer a valuable lens through which to explore the development of philosophical thought in the ancient world. While not typically classified as a philosopher in the traditional sense, his teachings resonate with themes central to early Greek philosophy, suggesting a possible cross-pollination of ideas across the ancient Near East.

Zarathushtra’s emphasis on ethical conduct, personal responsibility, and the eternal struggle between good and evil finds parallels in the writings of figures like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. His concept of Asha, encompassing truth, righteousness, and cosmic order, shares common ground with the Greek concept of Logos, the underlying principle of reason and order in the universe. This suggests that Zarathushtra might be considered a “proto-philosopher” — a thinker whose ideas laid the groundwork for more formalized philosophical systems that would emerge in later centuries.

Examining Zarathushtra through this lens allows us to appreciate him not just as a religious innovator but as a pivotal figure in the broader tapestry of ancient intellectual history. His contributions to ethical thought, cosmology, and the exploration of good and evil deserve recognition alongside those of his Greek counterparts, enriching our understanding of the interconnectedness of intellectual currents in the ancient world.

VII. The Feminine Divine in Zoroastrianism

In contrast to many ancient religions that often relegated female deities to subordinate roles, Zoroastrianism offers a more nuanced perspective on the feminine aspect of the divine. While Ahura Mazda stands as the supreme God, female divinities play significant roles in maintaining cosmic order and guiding humanity toward righteousness.

Spenta Armaiti, often translated as “Holy Devotion” or “Loving Piety,” embodies the virtues of faith, humility, and loving service. She is depicted as a protector of the earth and a guide for souls entering the afterlife. Ashi, representing “Reward,” “Prosperity,” or “Good Fortune,” embodies abundance, fertility, and the blessings that come from living a righteous life. She is often portrayed alongside Arштаtat, symbolizing wholeness and immortality.

The prominence of these female divinities suggests that Zarathushtra’s teachings may have challenged traditional gender roles prevalent in his time. By embodying essential virtues and wielding influence over both the spiritual and material realms, these goddesses offer a more balanced and inclusive perspective on the nature of the divine.

VIII. The Avesta: The Sacred Tapestry of Zoroastrianism

Central to the faith and practice of Zoroastrianism is the Avesta, a collection of sacred texts believed to contain the revealed wisdom of Ahura Mazda, transmitted through the prophet Zarathushtra. The Avesta, however, is not a single book but rather a compilation of scriptures composed over centuries, reflecting the evolving understanding and practices of the Zoroastrian community.

The Avesta, in its present form, comprises two main sections:

The Yasna: The most sacred portion of the Avesta, the Yasna (“Worship” or “Sacrifice”) serves as the liturgical core of Zoroastrian ritual practice. It contains prayers, hymns, and instructions for performing the yasna ceremony, a central act of worship involving fire offerings and the recitation of sacred verses.

- The Gathas: Within the Yasna are enshrined the 17 Gathas (“Songs” or “Hymns”), believed to be the oldest and most sacred portion of the Avesta, containing the direct utterances of Zarathushtra himself.

The Khorda Avesta: Literally the “Smaller Avesta,” this section serves as a guide for daily life and devotion. It includes prayers for various occasions, hymns to different divinities, and instructions for ethical conduct and ritual purity. Prominent texts within the Khorda Avesta include:

- The Visperad: A collection of invocations and litanies praising various aspects of creation.

- The Yashts: Hymns dedicated to specific divinities, celebrating their attributes and seeking their blessings.

- The Vendidad: A complex text dealing with ritual purity, laws of hygiene, and the avoidance of pollution, often seen as reflecting later additions and interpretations.

The Avesta, passed down through generations of priests and scholars, has faced its share of challenges and transformations. The original Avestan language, while related to Sanskrit, gradually faded from common use, necessitating translations and commentaries to preserve its teachings. The Arab conquest of Persia in the 7th century CE led to the destruction of many Avestan texts, leaving the surviving manuscripts as precious fragments of a once more extensive religious corpus.

Despite these challenges, the Avesta has retained its central role in Zoroastrian life, serving as a source of spiritual guidance, ritual practice, and ethical reflection for centuries. The task of interpreting its ancient verses, however, remains an ongoing process, with each generation of scholars and priests bringing new insights to bear on understanding its message for their time.

IX. Zoroastrianism Today: A Faith of Ancient Roots and Modern Relevance

Despite its ancient origins, Zoroastrianism continues to thrive in the 21st century, a testament to the enduring power of its teachings and the resilience of its communities. While no longer the dominant religion of a vast empire, Zoroastrianism survives as a vibrant minority faith, with communities scattered across the globe, each facing unique challenges and contributing to the evolving tapestry of this ancient tradition.

India: India is home to the largest Zoroastrian population in the world, primarily concentrated in Mumbai and surrounding areas. Known as Parsis (“Persians”), they descend from Zoroastrians who sought refuge in India following the Arab conquest of Persia. The Parsis have integrated successfully into Indian society while maintaining their distinct religious and cultural identity. They have excelled in various fields, including business, philanthropy, and the arts, and played a significant role in India’s economic and social development.

Iran: A smaller Zoroastrian community persists in Iran, the land of their faith’s origin. They have faced challenges over the centuries, including periods of persecution and pressure to convert to Islam. Despite these difficulties, they have maintained their traditions and places of worship, preserving a vital link to their ancient heritage.

Diaspora Communities: Zoroastrian communities have also emerged in North America, Europe, Australia, and other parts of the world, primarily due to migration patterns in the 20th century. These communities grapple with the joys and challenges of maintaining their faith and cultural practices in new lands, often finding creative ways to adapt to different contexts while preserving their heritage for future generations.

Zoroastrianism in the 21st century faces a number of challenges:

- Declining Numbers: Like many minority religions, Zoroastrianism faces the challenge of declining birth rates and assimilation into larger, dominant cultures.

- Intermarriage: Intermarriage with individuals outside the faith raises complex questions about identity and the transmission of religious traditions to future generations.

- Preservation of Traditions: Maintaining ancient rituals, languages, and scriptures in a rapidly changing world requires ongoing effort and adaptation.

Despite these challenges, Zoroastrianism demonstrates remarkable resilience and adaptability:

- Renewed Interest and Scholarship: Scholarly interest in Zoroastrianism has surged in recent decades, leading to new translations of its scriptures, interpretations of its teachings, and explorations of its history and influence.

- Interfaith Dialogue: Zoroastrians have been active participants in interfaith dialogue, building bridges of understanding and cooperation with other religious communities.

- Social Activism: Drawing on their faith’s emphasis on ethical living and social responsibility, many Zoroastrians are active in promoting peace, environmental sustainability, and social justice.

Zoroastrianism stands as a testament to the enduring power of ancient wisdom to speak to contemporary concerns. Its emphasis on ethical conduct, personal responsibility, and the pursuit of truth resonate deeply in a world grappling with complex ethical dilemmas. Its message of hope, embodied in the belief in the eventual triumph of good over evil, offers comfort and inspiration in times of uncertainty. As Zoroastrians continue to navigate the challenges of the 21st century, their faith, rooted in the teachings of a prophet who lived millennia ago, continues to offer a timeless path toward a more just and compassionate world.

- Star Ring Trends: Etsy vs Amazon - March 28, 2025

- Boost Pollinator Habitats: Baby Blue Eyes Sustainable Farming Guide - March 28, 2025

- Protect Big Black Bears: Effective Conservation Strategies - March 28, 2025