Get ready to dive into the captivating world of World Systems Theory in AP Human Geography! This theory offers a unique lens through which we can analyze the interconnectedness of nations, cultures, and economies on a global scale. We’ll explore how power dynamics and historical forces, like colonialism, contribute to global inequality. Buckle up for an exciting journey as we unravel the complexities of our interconnected world!

World Systems Theory in AP Human Geography

Have you ever wondered why certain countries seem to flourish economically while others struggle to make ends meet? World Systems Theory attempts to shed light on this global disparity by examining the world as a single, interconnected economic system rather than viewing countries as isolated entities. This theory posits that nations are engaged in a complex web of relationships characterized by power imbalances.

The Ups and Downs of Global Power

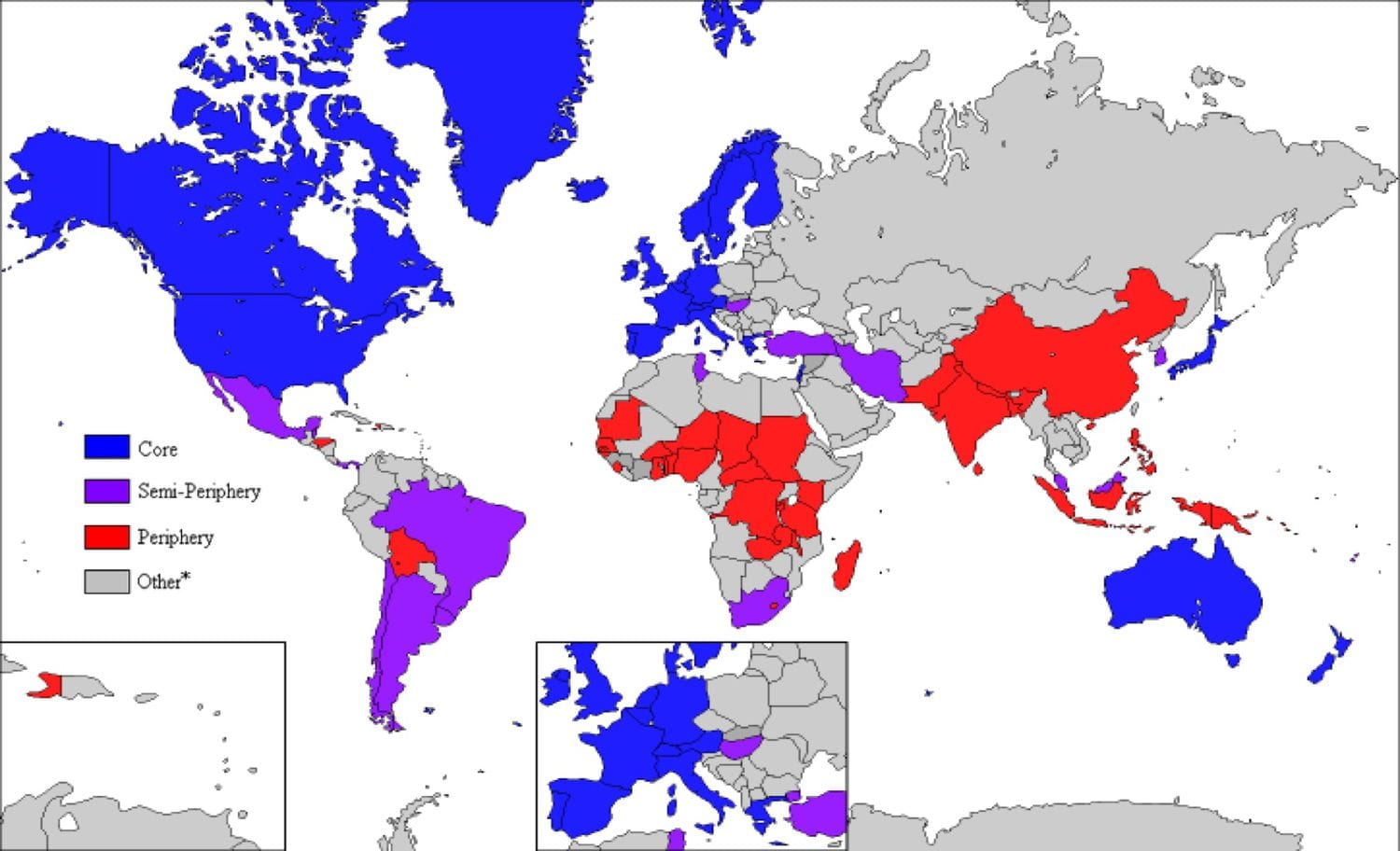

At the apex of this global power structure are the core countries. These economic powerhouses, such as the United States, Japan, and many European nations, boast advanced technologies, stable governments, and significant influence over global trade. Essentially, they hold a dominant position within the world system.

On the other end of the spectrum lie the peripheral countries. These nations frequently provide raw materials, such as oil or minerals, to the core countries. Lacking robust industrial sectors and often grappling with economic instability, they may find themselves reliant on core countries for employment and income.

Occupying a middle ground are the semi-peripheral countries, which can be likened to the “middle class” of the world system. Countries like Brazil, China, and India exemplify this category. These nations are experiencing industrialization, economic growth, and are actively striving to secure a more prominent position within the global market. However, they often navigate a delicate balance between their own development and the influence exerted by core countries.

The Enduring Legacy of History

World Systems Theory doesn’t just focus on the present; it digs deep into the past. It suggests that the global economic order we see today is a product of historical forces, particularly colonialism. Centuries ago, European powers colonized vast swathes of the globe, often exploiting resources and labor in the regions they dominated. Some experts believe this historical context helps to explain why certain countries continue to wield significant global influence.

Navigating a Complex World

While World Systems Theory provides a valuable framework for comprehending global inequality, it’s important to remember that it’s a model, not a crystal ball. There’s ongoing debate about the nuances of how this system operates and whether its inherent power imbalances can be overcome.

Some critics argue that the theory might be overly simplistic in its categorization of countries. They point to examples like South Korea, which transitioned from a peripheral nation to a major economic player, as evidence that countries are not always confined to fixed roles.

The future of the global economic system remains uncertain. Will core countries maintain their dominance, or are we witnessing a shift in global power dynamics, perhaps with the rise of economic giants like China? As you delve deeper into AP Human Geography, continue to engage with these complex global issues and develop your own insights into the intricate workings of our world.

What is the World Systems Theory in Geography?

The concept of interconnectedness lies at the heart of how we understand our world today. The World Systems Theory, developed by sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein, offers a framework for comprehending this interconnectedness, particularly within the realm of economics. Wallerstein envisioned the world economy not as a collection of independent states, but as a singular, integrated system.

To illustrate his theory, Wallerstein used the analogy of a pyramid, dividing countries into three primary categories based on their level of economic development, political influence, and overall standard of living:

- Core Countries: Occupying the top tier of the pyramid are the core countries—global economic powerhouses like the United States, Japan, and many Western European nations. These nations typically boast advanced industrialization, robust technological innovation, and significant political sway on the world stage.

- Periphery Countries: Forming the base of the pyramid are the periphery countries. These nations, often located in parts of Africa, Latin America, and Asia, tend to be less industrialized and reliant on exporting raw materials, such as oil, minerals, or agricultural products, to core countries.

- Semi-Periphery Countries: Positioned between the core and periphery are the semi-periphery countries. Acting as a bridge between the two, these nations often display a blend of characteristics. They may be experiencing rapid industrialization and economic growth but haven’t yet attained the global dominance of core countries. China, India, and Brazil serve as good examples of semi-periphery nations.

One of the most important aspects of World Systems Theory is its acknowledgment that this system is not static. Countries can transition between levels, although upward mobility is often a gradual and complex process.

This dynamic interplay between core, periphery, and semi-periphery countries is a subject of great interest to geographers. They study how the location of resources, historical patterns of colonialism, and global trade networks contribute to a country’s position within the world system.

World Systems Theory has faced its share of criticism, with some arguing that it oversimplifies the complexities of the global economy. Critics point out that the theory doesn’t always fully account for the role of international organizations or the influence of cultural factors.

Despite these criticisms, World Systems Theory provides a valuable framework for examining how nations are interconnected and how historical legacies continue to shape global power dynamics. It encourages us to think critically about the interconnectedness of globalization, inequality, and the distribution of power and resources in our world today.

What Does World Systems Theory Believe?

Imagine a world where the global economy operates as a single, interconnected entity rather than a collection of independent nations. That’s the premise of World Systems Theory. At its core (pun intended!), this theory attempts to explain how different countries fit into this global system and the roles they play.

Rather than viewing all countries as equal players, World Systems Theory suggests a hierarchy—a global power structure where some nations hold more influence than others. Within this hierarchy, we find:

- Core Countries: At the top of the hierarchy stand the core countries, often characterized by their wealth, industrial prowess, and political clout. These nations, such as the United States, Japan, and several Western European countries, often shape global trade, technology, and even cultural trends.

- Periphery Countries: At the other end of the spectrum lie the periphery countries. These nations, often located in parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, may be less developed and rely heavily on core countries for investment, technology, and trade. This relationship can sometimes result in periphery countries supplying resources and labor at costs that benefit core countries more than their own.

- Semi-periphery Countries: Occupying a middle ground are the semi-periphery countries, embodying a blend of characteristics found in both core and periphery nations. They might be experiencing rapid industrialization and economic growth but haven’t yet attained the global dominance of core countries. China, India, and Brazil exemplify this category.

World Systems Theory suggests that this system is not fixed; countries can, over time, move up or down this global hierarchy. However, upward mobility often involves overcoming significant obstacles, particularly when it comes to challenging the established economic and political order.

While the theory primarily centers on economic factors, it is essential to recognize that the real world is far more intricate. Critics argue that World Systems Theory doesn’t always fully account for the influence of cultural and political dynamics or the role of non-state actors like multinational corporations.

Even with these criticisms in mind, World Systems Theory provides a valuable lens for examining global power dynamics and understanding the persistent economic inequalities we witness in the world today. It encourages us to think critically about how historical patterns, like colonialism, continue to influence relationships between nations and why bridging the gap between the world’s wealthiest and poorest countries remains an ongoing challenge.

What Are the Three Categories of the World Systems Theory?

World Systems Theory seeks to explain global inequality by examining the interconnectedness of nations within a hierarchical global economic system. This system, according to the theory, is not a level playing field; rather, it’s characterized by power imbalances that favor certain countries over others.

Developed by sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein, World Systems Theory categorizes countries into three primary groups:

- Core Countries: Think of core countries as the “heavy hitters” of the global economy. They are typically characterized by:

- Economic Powerhouse: High levels of industrialization, advanced technology, and control over global finance.

- Political Influence: Strong governments, significant military capabilities, and substantial influence in international affairs.

- High Standard of Living: Citizens often enjoy high levels of education, healthcare access, and overall quality of life.

- Examples: The United States, Canada, Japan, and many Western European countries.

- Peripheral Countries: On the other end of the spectrum are peripheral countries. These nations often:

- Supply Raw Materials: Rely heavily on exporting raw materials, such as minerals, agricultural products, or cheap labor, to core countries.

- Limited Industrialization: May struggle with developing their industrial sectors, leading to dependence on manufactured goods from core countries.

- Economic Instability: Can experience economic vulnerability, high levels of poverty, and political instability.

- Examples: Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, parts of Southeast Asia, and some Latin American nations.

- Semi-Peripheral Countries: Bridging the gap between core and periphery countries are the semi-peripheral nations. These countries often exhibit characteristics of both, making them a fascinating area of study:

- Industrializing: They are actively undergoing industrialization and economic growth.

- Aspiring for More: They aim to achieve greater economic and political influence on the world stage.

- Vulnerable to Exploitation: They may still be susceptible to exploitation by core countries but might also engage in exploitative practices toward periphery countries.

- Examples: China, India, Brazil, Mexico, and South Africa.

It’s Not a Perfect System (or World):

It’s crucial to remember that the lines between these categories are not always absolute. The real world is far more nuanced, and some countries may exhibit characteristics of multiple categories. Additionally, World Systems Theory has been criticized for potential oversimplification and for not always fully accounting for cultural, political, or environmental factors.

Despite these criticisms, World Systems Theory provides a valuable framework for understanding global inequality. It reminds us that a country’s economic reality is often intertwined with its historical relationship with other nations, especially within the context of colonialism and the lasting legacies of those power dynamics.

How Does World Systems Theory Seek to Explain Global Economic Inequality?

World Systems Theory tackles the complex issue of why some countries seem perpetually stuck on the winning side of the global economic game while others remain mired in poverty. The theory doesn’t shy away from pointing out the inherent unfairness woven into the fabric of the global economic system.

Here’s how World Systems Theory explains persistent global economic inequality:

- History Casts a Long Shadow: The theory emphasizes that understanding current economic realities necessitates examining the long reach of history, particularly the impact of colonialism. The wealth accumulated by many core countries was often built upon exploiting the resources and labor of colonized nations. This historical legacy continues to shape global power dynamics today.

- Capitalism Takes Center Stage: World Systems Theory emphasizes that the global economy operates within a capitalist framework where profit is paramount. Core countries, seeking to maximize profits, often establish trade relationships that benefit their own economies while potentially hindering the growth of peripheral nations. This can involve extracting resources cheaply from periphery countries or exploiting lower wages, further widening the economic gap.

- Power Dynamics Are Key: The theory highlights that the hierarchical structure of the global economic system, with core countries at the top and periphery countries at the bottom, is not merely a random arrangement. This structure reflects and reinforces power imbalances. Core countries, with their economic and political clout, often set the terms of global trade, dictate rules for international finance, and hold significant influence in international organizations, making it challenging for periphery countries to break free from cycles of dependence and inequality.

Key Takeaways from World Systems Theory:

- The global economic playing field is inherently unequal, with the benefits of globalization not shared equitably.

- Historical injustices, particularly colonialism, continue to shape global economic relationships today.

- Understanding power dynamics is crucial to comprehending why closing the gap between the world’s richest and poorest countries remains a significant challenge. It’s not just about individual countries “working harder”; it’s about addressing the systemic issues of power imbalances, exploitation, and unequal access to opportunity embedded within the global economic system.

It’s important to acknowledge that while World Systems Theory offers a valuable framework for understanding global inequality, it is not without its critics. Some argue that it focuses too narrowly on economics and doesn’t fully account for other contributing factors, such as internal political dynamics within countries, cultural influences, or environmental challenges.

What is the World Systems Theory in AP Human Geography?

In AP Human Geography, we explore the intricate ways humans interact with and shape the world around them. World Systems Theory provides a compelling lens through which we can analyze the interconnectedness of nations and the uneven distribution of wealth and power on a global scale.

Here’s a breakdown of the key concepts of World Systems Theory within the context of AP Human Geography:

- Interconnectedness: At its core, World Systems Theory emphasizes that we cannot understand individual countries in isolation. The global economy is a vast and complex web of relationships, and a nation’s economic reality is often intertwined with its historical and current relationships with other countries.

- Hierarchy: The theory posits a hierarchical structure within this global system, with countries classified into three main categories based on their economic and political power:

- Core Countries: These nations, such as the United States, Japan, and many Western European countries, wield significant economic and political influence. They typically boast advanced industrialization, technological innovation, and control over global finance.

- Peripheral Countries: These nations, often located in parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, often occupy a less powerful position within the global system. They may rely heavily on core countries for trade, investment, and technology, and often provide raw materials and labor.

- Semi-Periphery Countries: Bridging the gap between core and periphery, these nations, such as China, India, and Brazil, demonstrate characteristics of both. They are industrializing and experiencing economic growth but may still be subject to exploitation by core countries.

- Unequal Exchange: World Systems Theory argues that this hierarchical system is not simply a result of some countries being “more developed” than others. This unequal exchange allows core countries to maintain their economic dominance while potentially hindering the growth of periphery nations.

- Historical Context Matters: The theory emphasizes that understanding current global inequalities requires examining historical power dynamics, particularly the enduring legacy of colonialism. The wealth accumulated by many core countries was often built, in part, upon exploiting the resources and labor of colonized nations.

World Systems Theory in Action:

World Systems Theory encourages us to look beyond national borders and examine the global forces that shape economic development, migration patterns, and even cultural trends. It provides a framework for analyzing:

- Why certain countries struggle to break free from cycles of poverty and dependence.

- How historical patterns of colonialism continue to influence global power structures.

- The potential consequences of globalization, both positive and negative, for different countries.

Criticisms and Ongoing Debate:

It’s important to note that World Systems Theory is not without its critics. Some argue that:

- It oversimplifies a complex world by dividing countries into neat categories that may not always reflect the nuances of global interactions.

- It focuses too heavily on economics and doesn’t fully consider other factors, such as cultural influences, technological innovation, or environmental challenges, that contribute to global inequality.

Despite these criticisms, World Systems Theory remains a valuable tool for AP Human Geography students. By encouraging us to examine global power dynamics, historical legacies, and the interconnectedness of nations, it deepens our understanding of the complex world in which we live.

What is the Main Focus of World-Systems Analysis?

World-systems analysis is a way of looking at the world as one interconnected system, rather than a collection of individual countries. It emphasizes the historical development of a global capitalist system and the power relationships between different regions within this system.

Here’s a breakdown of the main areas of focus for world-systems analysis:

1. The Big Picture:

Instead of just focusing on individual countries, world-systems analysis encourages us to zoom out and look at the global economy as a whole. It suggests that what happens in one part of the world can have ripple effects that impact other regions, even if they seem geographically distant.

2. Power Imbalances:

World-systems analysis is particularly interested in understanding how power is distributed within this global system. It suggests that some countries and regions, often referred to as the “core,” have historically held more economic and political power than others on the “periphery.” This power imbalance, the theory argues, is not accidental; it’s a product of historical processes like colonialism and the ongoing dynamics of global capitalism.

3. The Core, Periphery, and Semi-Periphery:

You’ll often hear world-systems analysts talk about the “core,” “periphery,” and “semi-periphery” as key categories for understanding the global system:

- Core: These are typically wealthy, industrialized countries with strong institutions and significant influence on global affairs. Think of countries like the United States, Japan, or Germany.

- Periphery: These countries often have less developed economies and rely heavily on exporting raw materials to core countries. They may experience higher levels of poverty, inequality, and political instability. Think of some countries in parts of Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia.

- Semi-periphery: As the name suggests, these countries occupy a middle ground. They might have some industrial development but still face challenges in fully catching up with the core. They might also play a role in exploiting the periphery while simultaneously being exploited by the core. Think of countries like Brazil, China, or India.

4. Unequal Exchange:

A central concept in world-systems analysis is the idea of “unequal exchange.” This refers to patterns of trade and investment that tend to benefit core countries more than peripheral ones. For example, core countries might buy raw materials cheaply from the periphery, process them into higher-value goods, and then sell those goods back to the periphery at a much higher price.

5. Long-Term Change:

While world-systems analysis emphasizes the historical roots of the current global order, it also recognizes that the system is not static. Countries can move between categories (though upward mobility is often difficult), and new centers of economic and political power can emerge over time.

World-systems analysis offers a critical lens for understanding:

- The historical roots of global inequality.

- The challenges faced by developing countries trying to achieve economic growth and social progress.

- The potential for shifts in global power dynamics.

Remember, world-systems analysis is just one way of looking at the world. It has its critics, with some arguing that it oversimplifies complex realities or focuses too heavily on economic factors. However, it remains an influential approach, encouraging us to think beyond national borders and consider the interconnectedness of global processes.

What Are the Global Systems in Geography?

In the vast field of geography, we explore the intricate connections between people, places, and the environment. Examining these connections on a global scale leads us to the concept of global systems—intricate networks that operate across national boundaries, shaping our world in profound ways.

These systems are interconnected and influence each other, creating a complex web of relationships that impact everything from economic development to cultural exchange to environmental sustainability.

Let’s delve into some of the key global systems that geographers study:

- Economic Systems: These systems encompass the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services worldwide. Key aspects include:

- Global Trade: The exchange of goods and services between countries, influenced by factors like comparative advantage, trade agreements, and transportation networks.

- Financial Markets: The interconnected system of financial institutions, investors, and borrowers that facilitates the flow of capital around the world.

- Multinational Corporations: Companies that operate in multiple countries, often with complex supply chains and significant influence on the global economy.

- Political Systems: These systems involve the exercise of power and governance at a global level. Important elements include:

- International Organizations: Entities like the United Nations (UN), the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that play a role in shaping global cooperation and addressing international issues.

- Geopolitical Relations: The complex relationships between countries, often influenced by factors like national interest, ideology, history, and the distribution of power.

- Global Governance: The evolving framework of rules, norms, and institutions that attempt to manage global challenges and coordinate action on issues that transcend national borders.

- Cultural Systems: These systems involve the exchange of ideas, beliefs, customs, and traditions across the globe. Significant aspects include:

- Globalization of Culture: The spread of cultural elements, such as music, food, fashion, and ideas, across national boundaries, often facilitated by technology and migration.

- Cultural Diffusion: The process by which cultural traits spread from one region to another, through migration, trade, or communication.

- Cultural Homogenization/Heterogenization: The debate over whether globalization leads to cultures becoming more similar (homogenization) or more diverse (heterogenization).

- Environmental Systems: These systems encompass the interconnected natural processes that shape our planet. Critical areas include:

- Climate Change: The long-term alteration of temperature and weather patterns primarily caused by human activities, with global consequences for ecosystems, societies, and economies.

- Resource Depletion: The unsustainable use of natural resources, such as fossil fuels, forests, and water, leading to environmental degradation and potential conflicts.

- Biodiversity Loss: The decline in the variety of life on Earth, driven by habitat destruction, climate change, and other human activities, with consequences for ecosystem resilience and human well-being.

World Systems Theory: A Lens for Understanding Global Inequality:

Within this context of global systems, World Systems Theory emerges as a critical framework for analyzing global inequality. It argues that:

- The global economy is not a level playing field; instead, it’s characterized by a hierarchical structure where some countries benefit more than others.

- Historical processes, such as colonialism, have shaped this unequal system, giving certain countries advantages that persist today.

- This hierarchical structure is often categorized by:

- Core Countries: Wealthy, industrialized nations that wield significant global influence.

- Peripheral Countries: Less developed nations that often provide raw materials and labor to core countries.

- Semi-Peripheral Countries: Occupying a middle ground, these countries exhibit characteristics of both core and periphery nations.

By understanding these global systems and how they interact, geographers gain a deeper understanding of the complex forces that shape our world and the challenges and opportunities presented by increasing global interconnectedness.

What Is the System Concept in Geography?

In the intricate tapestry of geography, the “system concept” serves as a powerful tool for unraveling the complexities of our world. Instead of viewing geographic phenomena in isolation, the system concept encourages us to see the world as a network of interconnected parts—a giant puzzle where each piece influences and is influenced by the others.

Think of it this way: Imagine trying to understand a river without considering the mountains where it originates, the rainfall that feeds it, or the ecosystems that thrive along its banks. You’d only be seeing a tiny fraction of the story. The system concept encourages us to zoom out and appreciate the interconnectedness of it all.

Key Elements of the System Concept:

- Interdependence: The parts of a system are not isolated; they rely on each other in complex ways. A change in one part of a system can trigger a cascade of effects throughout the entire system.

- Inputs and Outputs: Systems receive inputs (matter, energy, information) from their surroundings and process those inputs to produce outputs. For example, a city receives inputs of food, energy, and people and produces outputs like goods, services, and pollution.

- Feedback Loops: Feedback occurs when the outputs of a system loop back to influence its inputs. Feedback can be:

- Positive: Reinforces or amplifies change within a system (e.g., melting ice caps reducing Earth’s reflectivity, leading to further warming and more melting).

- Negative: Counteracts or stabilizes change within a system (e.g., a thermostat turning the heater off when a room reaches a certain temperature).

- Equilibrium: Systems often strive for a state of balance or equilibrium, where inputs and outputs are relatively stable. However, this equilibrium is dynamic, meaning it can shift in response to changes in the system or its surroundings.

World Systems Theory: A Prime Example of System Thinking in Geography

World Systems Theory, a key concept in human geography, exemplifies system thinking in action. It views the global economy as a single, interconnected system where:

- Countries are not isolated entities but rather parts of a larger whole.

- Power imbalances and historical relationships, like colonialism, influence the flow of wealth and resources.

- Changes in one part of the system (e.g., a financial crisis in a core country) can have far-reaching impacts on other parts of the system (e.g., economic hardship in peripheral countries).

System Thinking in Action:

The system concept helps geographers analyze a wide range of phenomena, including:

- Climate Change: Understanding the complex interactions between the atmosphere, oceans, land surfaces, and human activities is crucial for addressing this global challenge.

- Urbanization: Cities are complex systems with intricate flows of people, resources, and information. System thinking helps us understand challenges like traffic congestion, pollution, and housing affordability.

- Globalization: This process of increasing interconnectedness is driven by flows of capital, goods, information, and people, all of which can be analyzed through a system lens.

By embracing the system concept, geographers gain a more holistic and nuanced understanding of the intricate connections that shape our world.

What Is Systems Theory in Geology?

In the realm of geology, where we delve into the Earth’s history, composition, and processes, “systems theory” provides a powerful framework for understanding the interconnectedness of our planet’s dynamic forces. Instead of studying geological phenomena in isolation, system theory encourages us to see Earth as a complex web of interacting parts.

Think of it this way: Imagine trying to comprehend the formation of a mountain range without considering the movement of tectonic plates, the forces of erosion, or the influence of climate. You’d only be scratching the surface of the story. Systems theory reminds us that Earth’s systems are intricately linked.

Earth as a System of Systems:

Geologists often describe Earth as a system composed of several interconnected subsystems, each with its unique processes and influences:

- Geosphere: The solid Earth, including rocks, minerals, and the processes that shape the Earth’s surface, such as plate tectonics, volcanism, and erosion.

- Atmosphere: The envelope of gases that surrounds our planet, influencing weather patterns, climate, and the distribution of heat.

- Hydrosphere: All the water on Earth, including oceans, lakes, rivers, groundwater, and ice, playing a crucial role in climate regulation, erosion, and the distribution of nutrients.

- Biosphere: All living organisms on Earth, from the smallest microbes to the largest whales, interacting with and influencing the other Earth systems.

Key Concepts in Systems Theory for Geology:

- Interconnectedness: A change in one Earth system can trigger a cascade of effects throughout the others. For example, volcanic eruptions (geosphere) can release gases into the atmosphere, influencing climate patterns and potentially impacting the biosphere.

- Feedback Loops: These occur when the output of one system becomes the input of another, creating a cycle of influence.

- Positive Feedback: Amplifies change, potentially leading to instability (e.g., melting ice sheets reducing Earth’s reflectivity, leading to further warming and more melting).

- Negative Feedback: Counteracts change, promoting stability (e.g., increased atmospheric CO2 leading to plant growth, which absorbs CO2 and helps to regulate the climate).

- Equilibrium: Earth’s systems strive for a state of balance, but this equilibrium is dynamic and constantly adjusting to changes in inputs, outputs, and feedback loops.

Examples of Systems Thinking in Geology:

- Plate Tectonics: This theory revolutionized geology by explaining how the Earth’s lithosphere (outermost layer) is divided into plates that move and interact, causing earthquakes, volcanic activity, and the formation of mountain ranges.

- Climate Change: Understanding climate change requires analyzing the complex interplay between the atmosphere, hydrosphere, geosphere, and biosphere, including factors like greenhouse gas emissions, solar radiation, and ocean currents.

- The Rock Cycle: This cycle describes the continuous transformation of rocks from one type to another through processes like weathering, erosion, sedimentation, burial, heat, and pressure—a prime example of how Earth’s systems interact over vast stretches of time.

Systems theory provides a powerful lens for geologists, allowing them to see the interconnectedness of Earth’s processes and appreciate how seemingly isolated events can have far-reaching consequences. By studying Earth as a system, we gain a deeper understanding of our planet’s history, its present state, and its potential future.

How Is World Systems Theory Used Today?

World Systems Theory, despite being developed several decades ago, remains remarkably relevant in today’s rapidly globalizing world. It serves as a valuable analytical tool for researchers, policymakers, and activists seeking to understand and address persistent global inequalities.

Here are some of the ways World Systems Theory is being used today:

- Explaining Global Inequality: The theory provides a framework for understanding why vast economic disparities persist between countries and regions. It highlights how historical power imbalances, such as colonialism, and the dynamics of the global capitalist system often benefit core countries at the expense of those on the periphery.

- Analyzing Migration Patterns: World Systems Theory helps to explain global migration trends, suggesting that people often move from peripheral countries, where opportunities are limited, to core countries, seeking better economic prospects and a higher standard of living. This movement of labor, however, can create new challenges and inequalities in both sending and receiving countries.

- Understanding Global Trade and Finance: The theory sheds light on the power dynamics that shape international trade agreements and financial flows. It raises concerns about whether international institutions, like the World Trade Organization (WTO), truly promote fair trade or whether they often reinforce existing inequalities by favoring the interests of core countries.

- Informing Development Policy: World Systems Theory has influenced development discourse by emphasizing that addressing poverty and inequality requires looking beyond individual countries and tackling the structural imbalances within the global economic system. It has led to calls for fairer trade practices, debt relief for developing countries, and greater investment in education, healthcare, and infrastructure in marginalized regions.

- Critiquing Globalization: While globalization has brought benefits to some, World Systems Theory underscores that these benefits are not evenly distributed. It highlights how globalization can sometimes exacerbate existing inequalities by concentrating wealth and power in the hands of a few while leaving many behind.

- Analyzing the Knowledge Economy: In today’s increasingly knowledge-based economy, World Systems Theory helps us understand the new forms of dependence and inequality that can emerge. For example, the concentration of research and development in core countries can create a “knowledge gap” that further disadvantages peripheral nations.

Examples of World Systems Theory in Action:

- Fair Trade Movement: This movement advocates for more equitable trade relationships between core and periphery countries, ensuring that producers in developing countries receive fair prices for their goods and work in decent conditions.

- Debt Relief Campaigns: Activists and organizations use World Systems Theory to argue for debt relief for heavily indebted poor countries, contending that these debts are often rooted in exploitative lending practices and hinder development efforts.

- Critiques of Structural Adjustment Programs: These programs, often imposed on developing countries by international financial institutions, have been criticized from a World Systems perspective for promoting policies that can exacerbate poverty and inequality.

While World Systems Theory provides a valuable framework, it’s essential to remember that the world is complex. The theory is not without its limitations, and some argue that it oversimplifies reality or doesn’t adequately account for other factors influencing global dynamics. Nevertheless, World Systems Theory remains a powerful tool for understanding the interconnectedness of our world, the challenges of global inequality, and the ongoing quest for a more just and equitable global order.

Don’t Forget to Explore Further!

Do you want to know more about the historical perspective on global stratification and evolution of the capitalist global system? Visit our page on world system theory to read more.

Many scholars also argue that the semi-periphery plays a crucial role in the capitalist world-system. Do you agree with them? You can visit our page on semi periphery ap human geography to have more information.

Interested in the critiques of this theory? You think what are the criticisms levied against Immanuel Wallerstein’s world system theory? Read the in-depth information on our page criticisms of wallerstein world system theory to know more about it.

Let me know if you have other questions.

- SYBAU See You Baby Meaning: Gen Z Slang Evolves - July 1, 2025

- Unlock Your Inner Youth: Lifestyle Secrets for a Vibrant Life - July 1, 2025

- Decode SYBAU Meaning: Gen Z Slang Explained - July 1, 2025