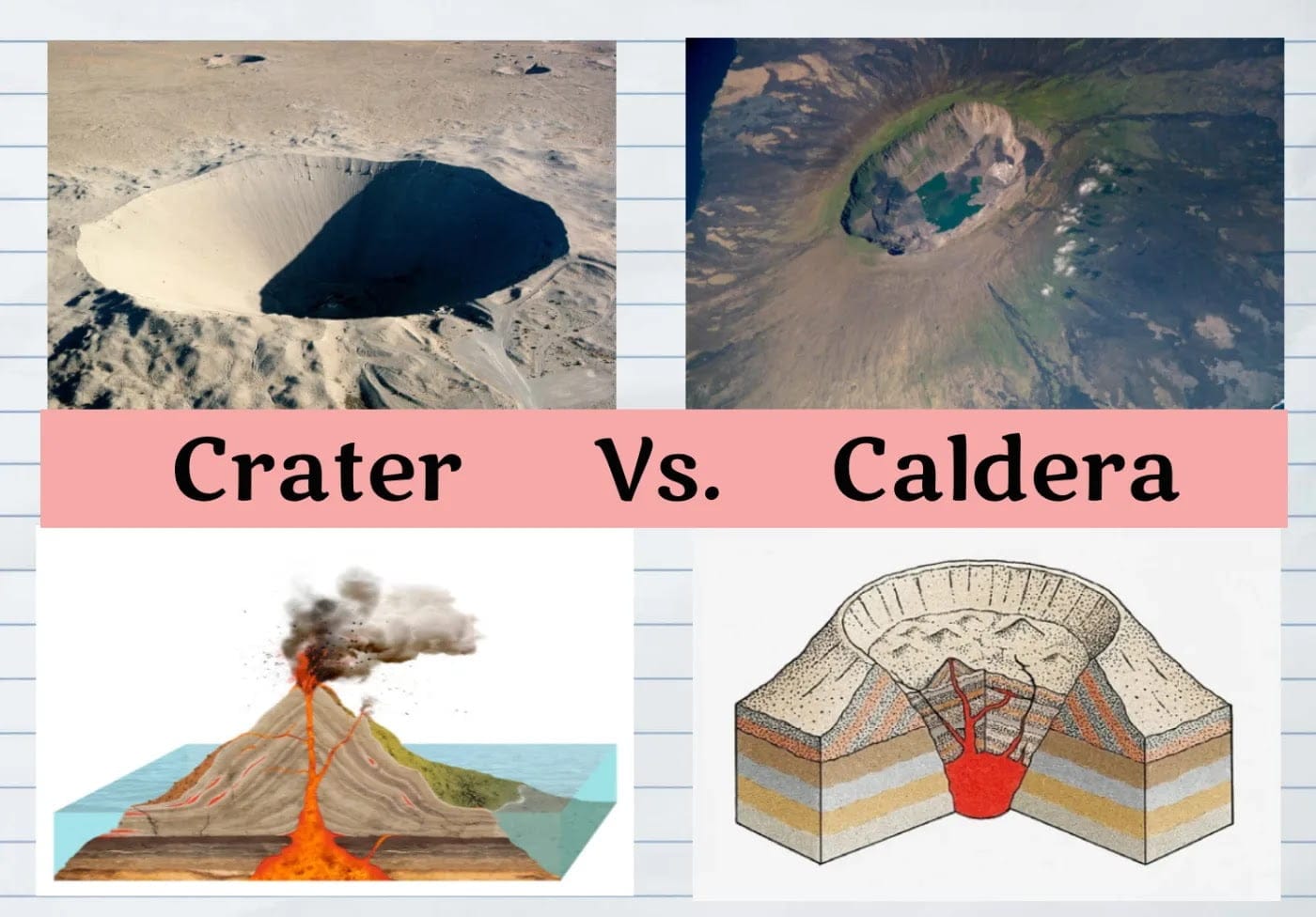

Welcome to the captivating world of geology! We’re about to delve into the intriguing differences between calderas and craters — two awe-inspiring scars etched upon our planet’s surface. Join us as we unearth the forces that shape these geological wonders and uncover the stories they tell about our Earth’s ever-evolving landscape.

What is the Difference Between a Caldera and a Crater?

When picturing a volcano, the image of a gaping hole at its summit likely springs to mind. While this is a common sight, these openings, known as craters or calderas, reveal vastly different tales about the volcano’s history.

Imagine a firecracker erupting — this spectacle somewhat mirrors the formation of a crater. As scorching magma surges from the volcano’s depths, a fiery shower of rock and ash is ejected, leaving behind a bowl-shaped scar, typically at the volcano’s peak. These craters are generally smaller, ranging from a few meters to hundreds of meters in diameter, resembling colossal bomb craters.

Now, envision a scenario far more dramatic. Picture a massive subterranean chamber brimming with magma that suddenly empties. The unsupported rock and earth above collapse inward, resulting in a colossal cave-in. This process gives birth to a caldera, a gigantic basin that can span kilometers — large enough to engulf entire cities!

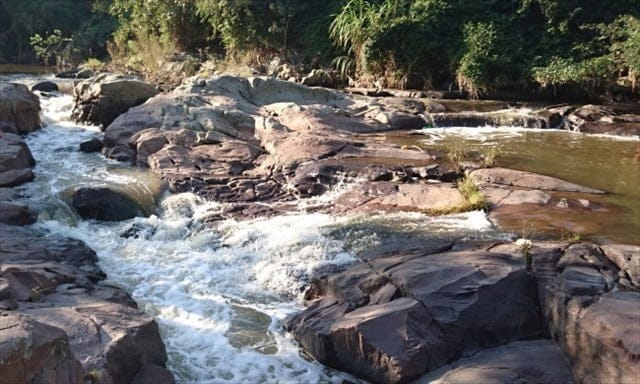

Here’s a table highlighting the key distinctions:

| Feature | Crater | Caldera |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Smaller (meters to hundreds of meters) | Much larger (kilometers wide) |

| Formation | Explosive eruption | Collapse of emptied magma chamber |

| Impact | Localized | Significant, altering the landscape |

Consider Crater Lake in Oregon — a breathtaking spectacle of deep blue water nestled within a massive, cliff-rimmed depression. This awe-inspiring feature is a caldera, formed thousands of years ago when the colossal volcano, Mount Mazama, erupted with such violence that its entire summit collapsed.

Calderas wield the power to dramatically reshape the surrounding landscape. Their formation can unleash earthquakes, trigger monstrous landslides, and spew immense ash clouds into the atmosphere, potentially altering river flows and birthing new lakes, much like Crater Lake. In contrast, craters are akin to minor dents, their impacts far less dramatic.

Scientists are continually studying the formation and evolution of these powerful geological features. Ongoing research explores various caldera collapse types, factors influencing their size and shape, and the potential long-term hazards they pose.

Therefore, the next time you encounter an image of a volcano marred by a gaping hole, remember that it’s not merely an empty space. It represents a window into the volcano’s explosive past – a crater or caldera whispering tales of fiery eruptions and colossal collapses.

What is the difference between a crater and a caldera quizlet?

While we’ve explored those impressive dips in our planet’s surface, how can one differentiate between a crater and a caldera? The key lies in their formation. Craters are born from explosions, while calderas emerge from epic collapses.

Imagine a volcano erupting with incredible force. The blast hurls fiery rocks and ash skyward, leaving a substantial dent in its wake. This, my friends, is a crater! Craters generally exhibit a circular shape, mirroring the outward burst that created them. Think of them as bowls — some shallow, others plunging deep into the Earth.

Now, let’s delve into calderas. Picture a volcano that has just expelled its massive underground magma reservoir in a single, colossal eruption. With its support system emptied, the ground above caves in, forming a gigantic sunken basin. These calderas dwarf craters in size, often stretching for miles! While they, too, can be circular, they may display more complex, irregular shapes due to the uneven nature of the ground collapse.

This table provides a handy summary:

| Feature | Formation | Size | Shape |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crater | Explosion | Smaller | Circular |

| Caldera | Collapse | Much Larger | Circular/Irregular |

Scientists believe that these dramatic events have shaped some of Earth’s most awe-inspiring landscapes. For instance, Yellowstone National Park resides within a massive caldera formed by a supervolcanic eruption millions of years ago. Quite remarkable, wouldn’t you say?

So, there you have it! Next time you come across a picture of a volcanic depression, impress your companions by identifying whether it’s a crater or a caldera.

What is the largest caldera in the world?

Having discussed the differences between calderas and craters, let’s now focus on those truly massive formations — calderas that dwarf craters. Imagine a gigantic bowl carved into the Earth’s surface, so vast it could swallow cities whole. This is the scale we’re dealing with when discussing some of these colossal calderas.

They can stretch for tens of kilometers, with some exceeding 50 kilometers in diameter. To put that into perspective, imagine driving across one of these behemoths — it would take hours just to traverse from one side to the other!

So, which caldera reigns supreme as the absolute largest? That honor belongs to the Yellowstone Caldera, nestled within the heart of Yellowstone National Park in the United States. This monstrous caldera stretches over a staggering 55 kilometers wide, surpassing the size of some countries! Its sheer size serves as a stark reminder of the immense power residing beneath Earth’s surface.

The existence of calderas like Yellowstone stands as a testament to the incredible forces that have shaped our planet over millions of years, offering a glimpse into the raw power of nature and reminding us of the incredible geological processes occurring beneath our feet.

What is the difference between a hole and a crater?

We’ve been exploring these fascinating geological formations, but let’s narrow our focus to a specific distinction: the difference between a hole and a crater. While one might assume they are synonymous, and there’s certainly overlap, understanding the nuances can deepen our appreciation for the powerful forces shaping our planet.

When a Volcano Takes a Dive: Introducing Calderas

Imagine a volcano that has experienced its fair share of eruptions. Its magma chamber, the underground reservoir for molten rock, is now largely depleted. The ground above, accustomed to this support, is suddenly left hanging. It’s akin to removing the legs from a table — collapse is inevitable.

This process gives rise to a caldera – a massive, often circular depression created by the inward collapse of a volcano. We’re talking about truly immense formations, sometimes stretching many kilometers across! Think of it as a gargantuan sinkhole, but instead of water erosion, it’s all about the drama of a volcano losing its internal scaffolding. Yellowstone National Park’s iconic landscape is a prime example, residing within a massive caldera that speaks to the sheer scale of these formations.

Explosive Birthmarks: The Story of Craters

Let’s shift our focus to a smaller scale. Picture a volcano, perhaps not as massive as one that spawned a caldera, but still harboring significant heat. This time, instead of a gradual collapse, we witness a violent explosion. Magma and gases blast through the volcano’s summit, creating a vent. The force of this eruption carves out a bowl-shaped depression – a crater.

Craters are like the telltale scars of a volcano’s fiery outbursts, typically smaller than calderas, averaging a few hundred meters across. However, their size can vary depending on the magnitude and intensity of the eruption. Interestingly, while calderas often form in dormant or extinct volcanoes, craters can indicate an active or recently active one. Spotting a crater suggests that a volcano might still have some fight left in it!

So, What’s the Takeaway?

- Calderas are the granddaddies of volcanic depressions – massive, formed by collapse, and often found in volcanoes past their prime.

- Craters, on the other hand, are the more dynamic youngsters, formed by explosive eruptions and potentially hinting at a volcano with some life left in it.

Next time you see an image of a volcanic landscape, impress your friends with your newfound caldera and crater knowledge!

But remember: Geology is full of surprises, and scientists are constantly making new discoveries. While we have a good grasp of how calderas and craters form, there’s always more to learn. Keep those curious minds engaged, and who knows what other geological wonders you might uncover!

When Can Calderas and Craters Be Seen Together?

We’ve established that calderas resemble giant, sunken bowls formed when a volcano essentially runs out of steam underground and collapses, while craters are more like punch bowls – smaller depressions left behind by explosive eruptions. One might assume that their different formation processes would preclude them from appearing together. However, nature often defies expectations!

Sometimes, we’re treated to a “two-for-one” deal with these volcanic features. Imagine a volcano erupting, leaving behind a sizable crater. Now, picture the volcano’s magma chamber below giving way, causing a massive collapse that engulfs the original crater. Voila! You have a caldera nestled within a larger, older crater. Talk about a dramatic landscape makeover!

One of the most stunning examples of this phenomenon is the formation of crater lakes. Picture a caldera nestled within a crater gradually filling with rainwater over time. The result? A breathtaking lake, often boasting incredibly clear blue waters, encircled by the dramatic walls of the caldera and the remnants of the original crater. Crater Lake in Oregon is perhaps the most famous example, a truly awe-inspiring sight.

Scientists are perpetually unraveling the complexities of volcanoes and the amazing landforms they create. It’s plausible that other ways exist for calderas and craters to coexist, and further research might reveal even more fascinating examples of this volcanic teamwork. So, the next time you encounter a picture of a volcano or a crater lake, take a moment to appreciate the powerful forces that shaped it. You might be observing the result of not one, but two distinct volcanic events.

- HelpCare Plus: Revolutionizing Affordable and Accessible Healthcare - December 29, 2024

- Boom & Bucket: Your Digital Marketplace for Used Heavy Equipment - December 28, 2024

- Ankle Bones Crossword Clue: Solutions, Tips & Anatomical Insights - December 28, 2024