Imagine the Founding Fathers gathered, debating the fate of a fledgling nation. Among them sits not only Washington and Franklin but a lesser-known yet influential figure: Noah Webster. This clergyman, a man of unwavering faith, would leave an indelible mark not only on America’s language but on its very soul.

A Legacy Forged in Language

Picture America’s infancy, a nation grappling with its identity. Enter Noah Webster, a man of the cloth driven by a profound belief in American exceptionalism. His interactions with the likes of George Washington and Ben Franklin fueled his vision for a uniquely American identity, one where language would serve as a unifying force.

Webster, however, was no mere orator confined to the pulpit. He understood the power of words, wielding them as tools to shape a nation. His “Blue-Backed Speller,” a modest book with a monumental impact, became a cornerstone of American classrooms, instilling a common language in a diverse and burgeoning population. But his ambitions didn’t stop there.

In 1828, Webster unleashed his magnum opus—the “American Dictionary of the English Language.” This was not just a lexicon; it was a declaration of linguistic independence, solidifying American English as distinct from its British counterpart. Through meticulous definitions imbued with moral and civic virtues, Webster’s dictionary became a testament to his vision of a virtuous and enlightened nation.

Webster’s influence extended far beyond the printed page. Recognizing the power of the press, he established America’s first daily newspaper, understanding its potential to inform and unite. A staunch advocate for intellectual property, he tirelessly lobbied for copyright laws, believing in the rights of authors to protect their creative works.

Today, Webster’s legacy extends far beyond dusty dictionaries relegated to library shelves. His emphasis on education and language reform continues to shape American society. He stands as a testament to the enduring power of words, a linguistic revolutionary who helped mold the language, identity, and educational spirit of a fledgling nation taking its first bold steps onto the world stage.

John Witherspoon: The Minister Who Signed His Name for Freedom

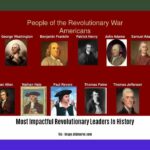

When we think of the Founding Fathers, names like Washington, Jefferson, and Franklin often dominate the conversation. But nestled among these giants of history is another figure, a man whose contributions were equally significant, yet whose name is often met with puzzled looks: John Witherspoon.

Born in Scotland in 1723, Witherspoon’s path to becoming an American revolutionary was anything but ordinary. He arrived in 1768, already a respected Presbyterian minister, to lead the College of New Jersey, the institution we now know as Princeton University. But Witherspoon was not content to remain within the walls of academia. He saw the brewing storm of revolution as a battle for freedom itself, a righteous cause worthy of his powerful voice.

Witherspoon became a member of the Continental Congress, that assembly of courageous individuals who dared to challenge an empire. And when the time came to declare their independence, Witherspoon, the only ordained minister present, added his name to the most iconic document in American history—the Declaration of Independence.

Which Founding Father was a clergyman?

John Witherspoon stands out as the only ordained minister among the Founding Fathers, bridging the gap between faith and the fight for American independence. While not all Founding Fathers adhered to the same denomination, Witherspoon’s fervent Presbyterianism underscored the significant influence of Christian principles on the era’s political thought.

Witherspoon’s influence wasn’t limited to politics and revolution. He understood that a new nation needed a strong foundation, and he believed education was the key. As president of Princeton, he championed a vision of education that extended beyond textbooks and lectures. Witherspoon sought to shape character, to foster a sense of civic duty, to prepare young minds to lead a free nation. For over two decades, he molded the minds of future generations, his legacy imprinted on the very fabric of American thought and leadership.

While history might not remember John Witherspoon with the same fanfare as some of his contemporaries, his impact on the birth of the United States is undeniable. He was a passionate advocate for freedom, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and a visionary educator who shaped the minds of future leaders. So, the next time you ponder the question, “Which Founding Father was a clergyman?” you’ll have your answer: John Witherspoon, the Scottish minister who left an indelible mark on the soul of a nation.

The Founding Fathers and the Search for Truth: Deism and Unitarianism

The religious beliefs of the Founding Fathers are often painted in broad strokes, but a closer look reveals a more complex and nuanced picture. Many of these men, influenced by the Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason and individual liberty, grappled with questions of faith and reason, exploring alternative perspectives like Deism and Unitarianism.

Who Are the Unitarian Founding Fathers?

Unitarianism, with its focus on reason and individual conscience, gained traction in the late 18th century. While direct declarations of Unitarian belief among the Founding Fathers are limited, several figures, through their writings and actions, suggest an affinity for this progressive faith.

John Adams, for example, publicly aligned himself with Unitarianism later in life. Evidence suggests that his wife, Abigail Adams, a leading voice of the era, also embraced Unitarian beliefs. Thomas Jefferson, though often associated with Deism, expressed views aligning with Unitarian principles, particularly in his emphasis on reason and his rejection of traditional Christian doctrines like the Trinity.

Which Founding Fathers Were Deists?

Deism, a philosophy that viewed God as a “Clockmaker” who created the universe but didn’t interfere with its workings, resonated with many Founding Fathers seeking to reconcile faith with reason.

George Washington, while never explicitly declaring himself a Deist, is believed to have leaned towards Deistic principles. He expressed a belief in a “Providence” governing the world but rarely participated in communion or emphasized traditional Christian doctrines.

Thomas Jefferson, a vocal advocate for the separation of church and state, openly identified as a Deist. He even created his own version of the Bible, removing passages he considered supernatural.

Benjamin Franklin, initially raised Puritan, embraced Deism later in life, advocating for religious tolerance and a government free from religious influence.

A Tapestry of Beliefs

It’s crucial to remember that the Founding Fathers represented a spectrum of religious beliefs. Categorizing them definitively as “Deist” or “Unitarian” can be overly simplistic. These men, products of their time, were influenced by a confluence of ideas.

The significance lies in recognizing how their exploration of Deism and Unitarianism contributed to a climate of religious tolerance and shaped the very foundations of American governance. The principles of individual conscience, religious freedom, and the separation of church and state enshrined in the U.S. Constitution stand as testaments to the enduring legacy of these often-overlooked beliefs.

Don’t Miss: Discover the powerful stories behind other pivotal moments in American history:

- Did you know that Emmett Till’s death photos were so horrifying that they were instrumental in galvanizing the Civil Rights Movement? Learn more about the emmett till death photos.

- The Ku Klux Klan’s ethnocentrism was a major factor in the increase of racial violence in the South. Find out more about was kuklux klan ethnocentrism.

- Voter fraud was rampant in the run-up to Kansas statehood. Read more about voter fraud with kansas statehood.

- Crypto Quotes’ Red Flags: Avoid Costly Mistakes - June 30, 2025

- Unlock Inspirational Crypto Quotes: Future Predictions - June 30, 2025

- Famous Bitcoin Quotes: A Deep Dive into Crypto’s History - June 30, 2025