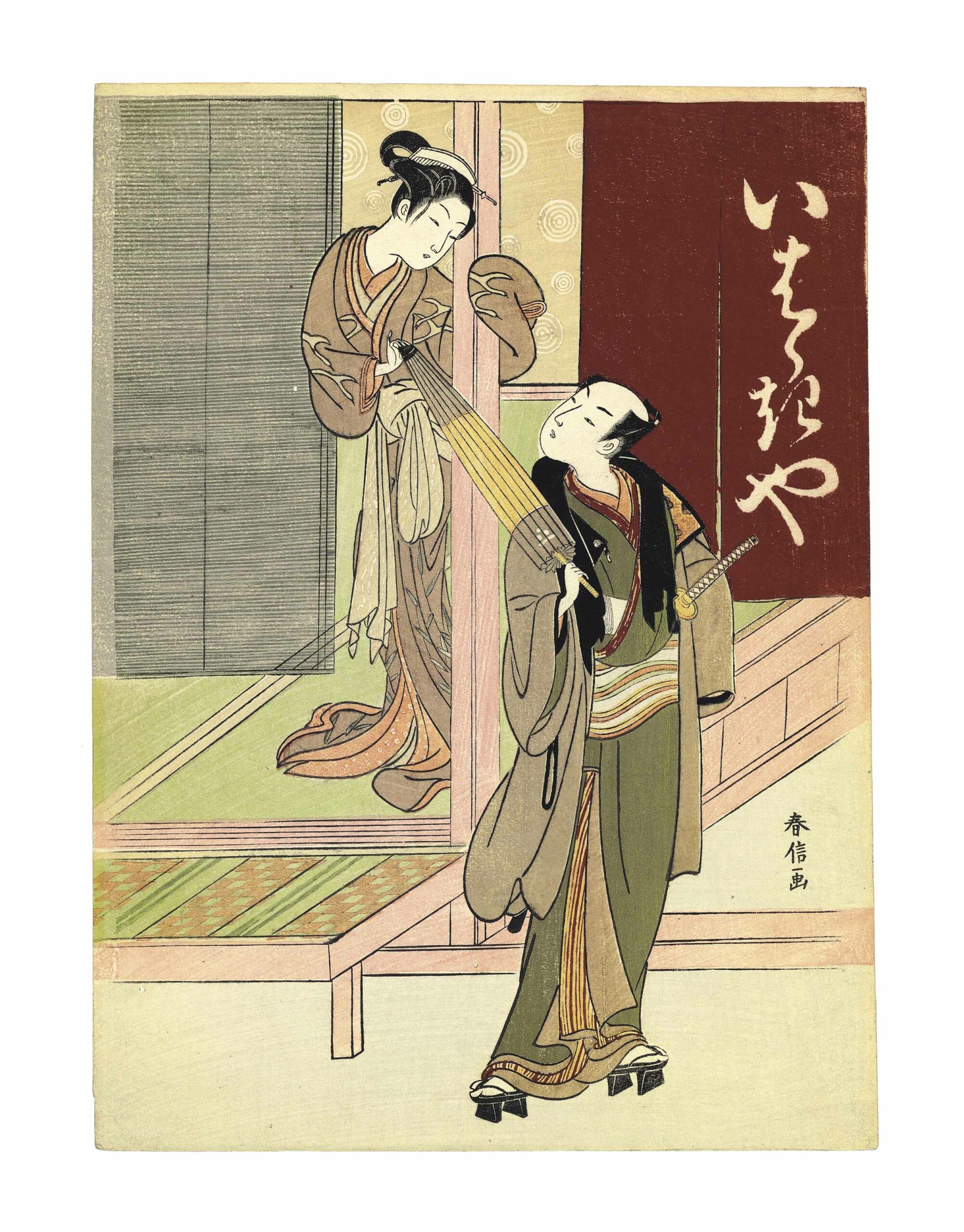

Ever wonder about those strikingly vibrant woodblock prints from old Japan? A key figure behind their creation is Suzuki Harunobu, a prominent artist of 18th-century Japan’s Edo period. Harunobu was a master of *ukiyo-e*, a style capturing the era’s “floating world,” and renowned for his innovative full-color prints, known as *nishiki-e*. This article explores Harunobu’s life, his transformative impact on Japanese art, and the enduring legacy of his colorful creations.

Harunobu’s Artistic Revolution

Suzuki Harunobu, active from roughly 1760 until his death in 1770, wasn’t just another ukiyo-e artist; he revolutionized the form. He spearheaded a vibrant shift in Japanese art, propelling it from a world of limited color palettes to one bursting with rich detail and hues.

The Dawn of Nishiki-e

Imagine a world of muted tones suddenly exploding into a kaleidoscope of color. That’s the impact of nishiki-e, meaning “brocade pictures.” This groundbreaking full-color printing technique, attributed primarily to Harunobu, transformed the landscape of ukiyo-e. Prior to 1765, woodblock prints may have incorporated a few colors, but they primarily relied on subdued tones and simple lines. Harunobu’s nishiki-e debuted with a series of elaborately printed calendars in 1765, commissioned by Edo’s wealthy elite to give as gifts. Suddenly, prints became windows to another world, depicting intricate details such as the soft sheen of silk kimonos and the subtle blush on a maiden’s cheek.

Harunobu’s Signature Style

Harunobu’s genius extended beyond technical innovation. His distinct artistic style emphasized delicate lines, graceful figures, and the subtle conveyance of emotion. A shy smile, a whispered secret, the rustle of silk – these were the nuances Harunobu captured. His mastery of suggestion allowed viewers to connect with his subjects’ emotions on a deeper level. His preference for soft pastels imbued his prints with a dreamlike quality, capturing fleeting moments with ethereal beauty.

Exploring Harunobu’s Themes

While renowned for his bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women, including courtesans), Harunobu’s subject matter was surprisingly diverse. He offered glimpses into everyday life in Edo (present-day Tokyo), portraying intimate moments and shared experiences among ordinary people: a quiet chat over tea, shared laughter, a stolen moment of affection. His sensitive portrayals of lovers, reflecting societal norms, also extended to the realm of shunga (erotic art). Furthermore, Harunobu drew inspiration from classical Japanese literature, weaving literary figures and themes into his visual narratives, enriching their meaning for those familiar with the stories.

A Lasting Legacy

Harunobu’s impact on ukiyo-e was profound and enduring. His nishiki-e innovation opened up new artistic possibilities, influencing subsequent artists like Torii Kiyonaga and Kitagawa Utamaro, who built upon his work. Much like the printing press democratized knowledge, nishiki-e made beautiful art accessible to a broader audience. Harunobu’s prints continue to resonate with viewers today, a testament to his artistic genius and the vibrant world he created.

Authenticating Japanese Woodblock Prints: A Comprehensive Guide

This section dives into the art of identifying authentic Japanese woodblock prints. Like detectives, we’ll examine clues hidden within the artwork to determine its genuine nature.

Deciphering the Lines

Start by examining the quality of the lines. Authentic woodblock prints, created by pressing paper against a carved woodblock, exhibit a distinctive crispness and clarity—like a freshly inked stamp. Reproductions often appear blurred or fuzzy, struggling to replicate the original’s fine details. Subtle variations in line thickness and ink density are hallmarks of a hand-printed original.

The Enigma of Edition Numbers

Edition numbers can be misleading. Most pre-1920 Japanese woodblocks were “open editions,” meaning there was no predetermined limit on the number of prints. So, an edition number on a supposedly antique print is a red flag. However, the absence of a number doesn’t guarantee authenticity.

The Paper Trail

The paper itself offers valuable clues. Its texture should align with the papermaking techniques of the print’s purported era. Experts can identify period-specific papers based on feel and appearance. Analyzing the paper fibers can reveal more about its age and source.

A Colorful History

Color is another key indicator. Early Japanese prints (pre-1765) typically used a limited color palette. The arrival of nishiki-e around 1765, spearheaded by Harunobu, ushered in full-color prints. A supposedly pre-1765 print bursting with color is likely a reproduction.

Flipping the Script: The Reverse Side

Examine the back of the print. Genuine woodblocks might reveal subtle texture variations from the woodblock itself. Reproductions, printed on smooth surfaces, typically lack this tactile quality.

Provenance: Tracing the Lineage

Provenance, the history of ownership, significantly enhances a print’s authenticity and value. While not all genuine prints have documented provenance, it’s a crucial factor to consider.

Seeking Expert Counsel

If you’re unsure about a print’s authenticity, consulting reputable auction houses, art appraisers, or specialist dealers is highly recommended. Their expertise is invaluable. Online resources like Ukiyo-e Search (ukiyo-e.org) can aid in reverse image searches and comparisons with established collections.

Decoding “Crow and Heron”: The Hidden Meaning in Harunobu’s Snow Lovers

Suzuki Harunobu’s Lovers Walking in the Snow isn’t just a beautiful image; it’s rich with symbolism. Let’s explore the possible interpretations of this intriguing piece.

Duality and Symbolism

The lovers’ contrasting black and white robes, reminiscent of a crow and a heron, likely symbolize duality—yin and yang, the interplay of opposites, perhaps even life and death. This striking contrast suggests a delicate balance within the relationship. The ai ai gasa (shared umbrella) visually connects the lovers, symbolizing their shared journey, their intertwined fate.

The Snowy Landscape

The snow itself is open to interpretation. Does it enhance the romance or add a melancholic tinge? It suggests purity, fragility, and the ephemeral nature of beauty, perhaps even hinting at a shroud or the journey towards the afterlife.

A Journey to Love Suicide?

Some scholars believe the print depicts a michiyuki, a lovers’ pilgrimage culminating in double suicide. While a somber interpretation, it adds another layer of complexity to the scene, imagining the couple’s quiet resolve and bittersweet tenderness.

Harunobu’s Mastery

Harunobu’s mastery of nishiki-e is evident here. He employs a restrained color palette to create a powerful visual impact. The simple composition, with the lovers as the focal point against the snowy backdrop, highlights his ability to evoke emotion through subtle means.

The Enduring Mystery

The true meaning of Lovers Walking in the Snow continues to intrigue. Its beauty lies in the unanswered questions and the multiple interpretations it invites. Harunobu’s genius lies in his ability to spark our imaginations centuries later. Ongoing research and new perspectives might further illuminate Harunobu’s intentions, reminding us that our understanding of art and symbolism is constantly evolving.

How Nishiki-e Works: Unveiling the Art of “Brocade Pictures”

Nishiki-e, meaning “brocade picture,” revolutionized Japanese woodblock printing by introducing vibrant multi-color designs. This technique, perfected by Suzuki Harunobu in the 1760s, involved the meticulous carving and precise alignment of multiple woodblocks to create stunning full-color images.

A Collaborative Process

Creating nishiki-e was a collaborative effort involving a designer, a carver, and a printer. The process began with the artist’s initial design, which served as the blueprint for every subsequent step. Then, the omohan, the key block, was carved outlining the image and registering the colors. This was followed by the carving of multiple color blocks, each corresponding to a specific area and hue.

Precision and Patience

Each color block was then inked with its designated color, demanding precise color matching and consistency. The printing process involved pressing each inked block onto the paper, layer by layer, using the omohan for perfect alignment. This meticulous process required patience and a steady hand to prevent smudging or overlapping.

From Elite Calendars to Popular Art

Initially used for elaborate calendars prized by Edo’s elite, nishiki-e quickly gained popularity, depicting a wide range of subjects from beautiful women and kabuki actors to landscapes and scenes from literature. This accessibility democratized art, bringing beautiful, colorful images to a wider public.

A Global Impact

Nishiki-e‘s influence transcended Japan’s borders, impacting artistic movements worldwide. Its use of vibrant colors and intricate designs likely influenced European Impressionism and Art Nouveau, though this remains a topic of ongoing scholarly discussion.

The Enduring Allure

Nishiki-e stands as a testament to human ingenuity and artistic vision. It offers a captivating glimpse into a bygone era, its stories told through a language of color and form. Ongoing research continues to explore technical challenges faced by these artisans, reminding us that nishiki-e is not merely a pretty picture; it’s a vibrant testament to a rich artistic and cultural history.

Sir Alfred Hitchcock Hotel

Sir William Crookes

- Unlock Filipino Culture: A Deep Dive into Traditions and Practices - April 23, 2025

- Unlock Spanish Culture: Insights & Opportunities Now - April 23, 2025

- White Spirit Uses & Substitutes: A Deep Dive for Pros & DIYers - April 23, 2025