Unlocking the Power of Association: Explore how respondent conditioning shapes our behaviors, from everyday habits to targeted therapies. This fascinating learning process, also known as classical or Pavlovian conditioning, explains how we develop automatic responses to various stimuli in our environment. From the aroma of freshly brewed coffee triggering a sense of alertness to the sound of a dentist’s drill inducing anxiety, respondent conditioning plays a significant role in shaping our experiences. This article delves into the mechanics of respondent conditioning, providing a comprehensive overview with real-world examples and exploring its diverse applications.

Are you preparing for the SERE 100.2 post-test? Familiarize yourself with the [SERE 100.2 Post Test Answers](https://www.lolaapp.com/sere-100-2-post-test-answers) before taking the test. For those interested in exploring mechanical engineering design, [Shigley’s Mechanical Engineering Design](https://www.lolaapp.com/shigley-s-mechanical-engineering-design) offers comprehensive insights and practical applications.

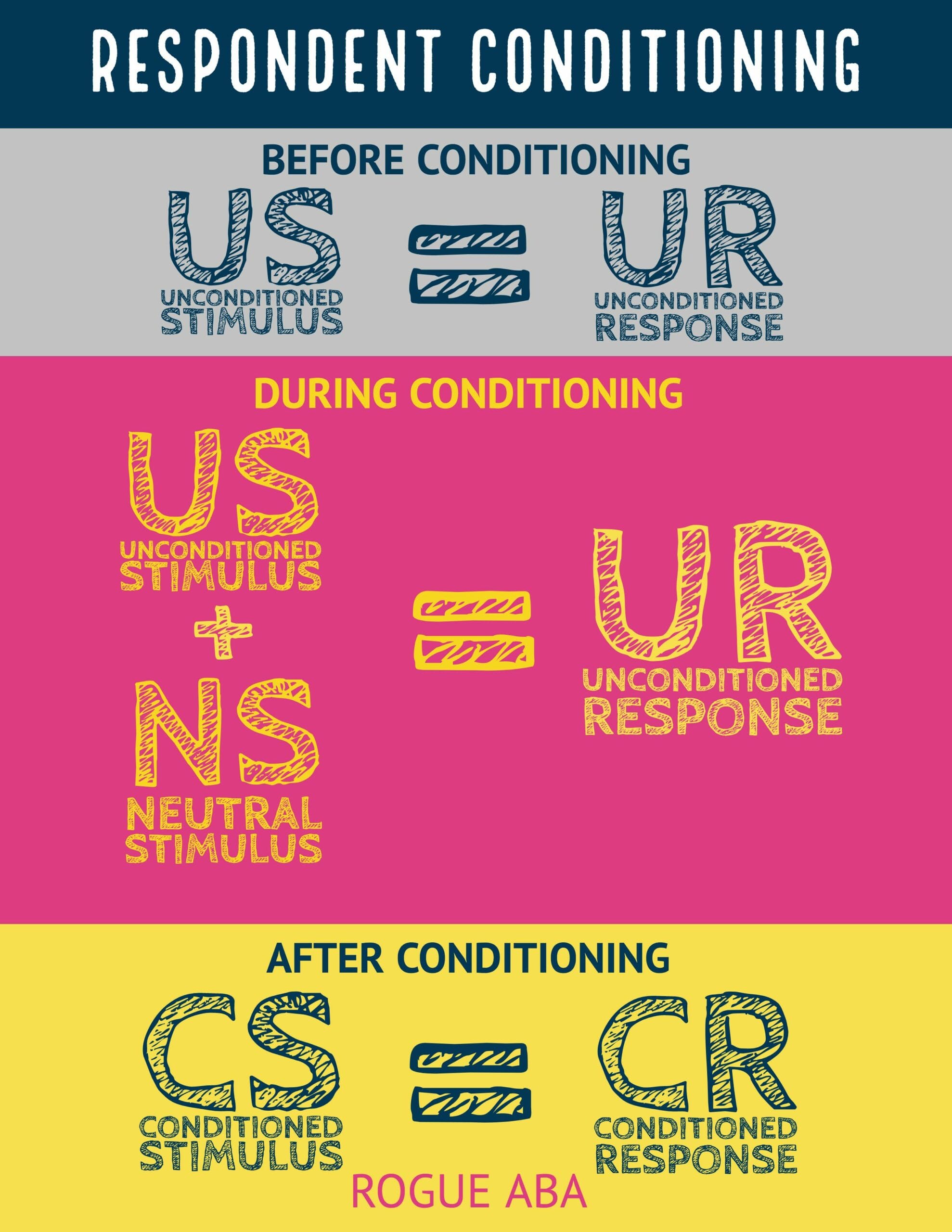

Deconstructing Respondent Conditioning: The Basics

Respondent conditioning is a learning process where an association is made between a previously neutral stimulus and a naturally occurring stimulus. The previously neutral stimulus eventually elicits the same response as the natural stimulus. Let’s break down the key components:

- Unconditioned Stimulus (US): A stimulus that naturally and automatically triggers a response. (e.g., food)

- Unconditioned Response (UR): The natural and automatic response to the unconditioned stimulus. (e.g., salivation)

- Neutral Stimulus (NS): A stimulus that initially does not elicit any specific response. (e.g., bell)

- Conditioned Stimulus (CS): The initially neutral stimulus that, after being repeatedly paired with the unconditioned stimulus, elicits a conditioned response. (e.g., bell after pairing with food)

- Conditioned Response (CR): The learned response to the conditioned stimulus. (e.g., salivation in response to the bell)

Pavlov’s Legacy: The Canine Experiment That Changed Psychology

Ivan Pavlov’s groundbreaking experiment with dogs laid the foundation for understanding respondent conditioning. He paired the ringing of a bell (NS) with the presentation of food (US) to dogs. Over time, the dogs began to salivate (CR) at the sound of the bell (CS) alone, demonstrating a learned association.

Beyond Pavlov: Modern Examples of Respondent Conditioning

Respondent conditioning isn’t confined to laboratories. It subtly influences our daily lives in countless ways. Here are some compelling examples:

Everyday Encounters

- Food Aversions: That bad sushi experience? The sushi (previously a neutral stimulus) is now a conditioned stimulus (CS) triggering nausea (CR). Your body has learned a powerful lesson.

- Allergies: The sight of pollen (CS) may trigger anxiety (CR) in anticipation of an allergic reaction, even before the actual physiological response.

- Waking Up to Your Alarm: The jarring sound of your alarm (US), initially a neutral stimulus, becomes associated with the need to wake up, eventually causing you to feel groggy and annoyed (CR) even before the alarm goes off.

- First Love: The scent of a specific perfume (CS) might trigger fond memories and positive feelings (CR) if it was worn by a past love.

Marketing and Media

- Advertising: Companies pair products (NS) with images of happiness and success (US) to elicit positive emotions (UR). Over time, you might unconsciously associate those good feelings (CR) with the product (CS), increasing your likelihood of purchasing it.

- Music and Emotions: A particular song (CS) can evoke strong emotions (CR) if it was playing during a significant life event. This can be joy, sadness, or even nostalgia.

- Celebrity Endorsements: Pairing a celebrity you admire (US) with a product (NS) can lead to a positive association (CR) with that product, influencing buying decisions.

Fears and Phobias

- Fear Conditioning: A child startled by a loud bark (US) may develop a fear of dogs (CS), even if the dog itself was not aggressive. This learned fear (CR) can persist into adulthood.

- Dental Anxiety: The sound of a dentist’s drill (CS), initially neutral, can trigger anxiety (CR) due to its association with past unpleasant experiences (US).

- Public Speaking Anxiety: Negative experiences (US) with public speaking can condition a person to experience anxiety (CR) simply by anticipating a presentation (CS).

Medical Applications

- Chemotherapy and Nausea: The smell of a hospital (CS) can trigger nausea (CR) in cancer patients who have undergone chemotherapy, as the smell becomes associated with the treatment’s side effects (US).

- Drug Tolerance: Repeated drug use in a specific environment (CS) can lead to the body anticipating the drug’s effects and triggering compensatory responses (CR), leading to tolerance.

Additional Examples

- Anticipation of Pain: Seeing a needle (CS) can trigger fear and anticipation of pain (CR) due to its association with past injections (US).

- Placebo Effect: A sugar pill (CS) can sometimes alleviate symptoms (CR) if the patient believes they are receiving actual medication, demonstrating the power of expectation and conditioning.

Respondent Extinction: Breaking the Association

What happens when we want to break a learned association? This is where respondent extinction comes in. By repeatedly presenting the conditioned stimulus (CS) without the unconditioned stimulus (US), the conditioned response (CR) gradually weakens. For example, someone with a dog phobia might undergo exposure therapy, gradually interacting with dogs in a safe environment until their fear response diminishes.

The Future of Respondent Conditioning: Unanswered Questions and Ethical Considerations

While much is understood about respondent conditioning, research continues. Some experts are exploring the role of awareness in conditioning and the long-term impacts of extinguished responses. Furthermore, ethical considerations are crucial, especially concerning the use of conditioning in advertising and other persuasive techniques. Understanding the power of respondent conditioning allows us to appreciate the complexity of human behavior and develop more effective therapeutic interventions.