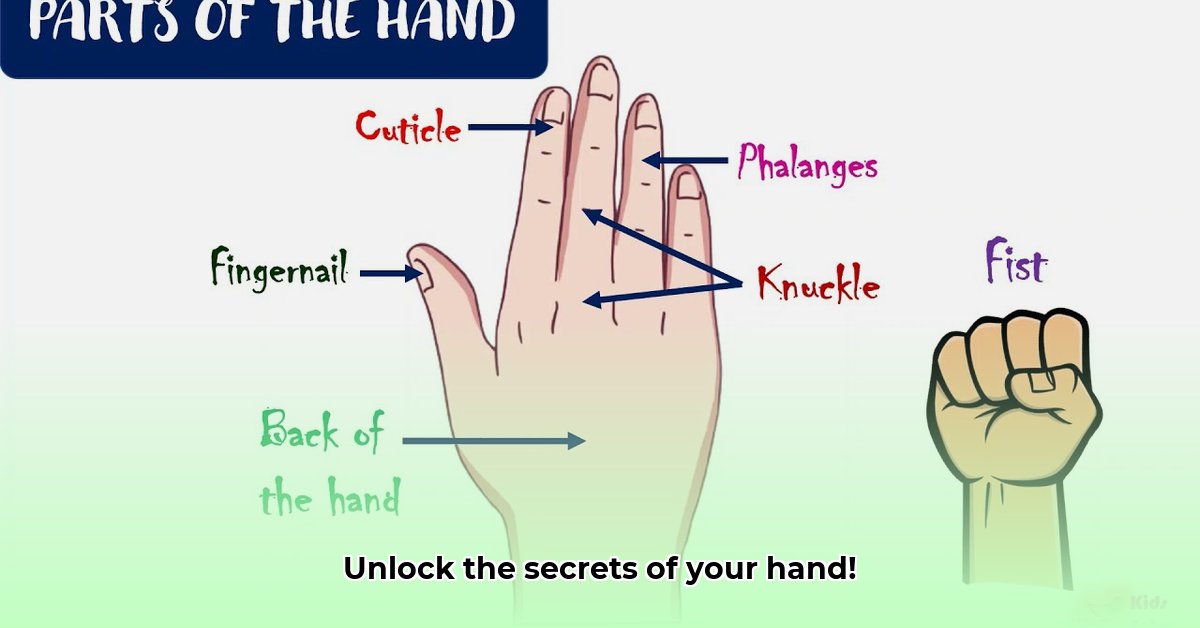

Our hands are remarkable instruments, enabling us to interact with the world in countless ways, from the delicate precision of a surgeon to the powerful grip of a weightlifter. This comprehensive guide delves into the fascinating anatomy of the hand, exploring the intricate interplay of bones, joints, muscles, and other structures that give rise to such dexterity. We’ll uncover the secrets behind the hand’s adaptability and explore its clinical significance. For a similar look at another complex appendage, check out this guide on foot anatomy.

The Architectural Marvel of the Hand: An Overview

The human hand, capable of both forceful grips and subtle manipulations, is a testament to evolutionary engineering. This intricate design involves a complex interplay of bones, joints, muscles, tendons, ligaments, nerves, and blood vessels. Understanding the hand’s multifaceted structure is crucial for appreciating its impressive capabilities. The hand’s 27 bones, the most in any single body part, provide a foundation for unparalleled dexterity.

Bones: The Foundation of Dexterity

The 27 bones of the hand are categorized into three groups:

- Carpals (Wrist Bones): Eight small, irregularly shaped bones form the wrist joint, providing stability and enabling a wide range of motion, including flexion, extension, and radial/ulnar deviation. The scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, pisiform, trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate work together to create a flexible yet strong base for the hand.

- Metacarpals (Palm Bones): Five elongated bones form the palm, connecting the wrist to the fingers. Numbered 1-5 starting from the thumb, each metacarpal provides structural support and serves as an attachment point for ligaments and muscles.

- Phalanges (Finger Bones): Fourteen bones form the fingers. Each finger has three phalanges – proximal, middle, and distal – except the thumb, which has only proximal and distal phalanges. This structure allows for intricate finger movements and precise manipulation of objects.

Joints: Articulating Movement

Joints, the points where bones meet, facilitate hand movement. Several types of joints contribute to the hand’s flexibility:

- Wrist Joint: This condyloid joint allows for flexion, extension, adduction, abduction, and circumduction.

- Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) Joints: These condyloid joints connect the metacarpals to the proximal phalanges, enabling finger spreading, flexion, and extension.

- Interphalangeal (IP) Joints: These hinge joints are located between the phalanges, allowing for finger bending and straightening. The thumb has one IP joint, while the other fingers have two (proximal and distal).

Muscles: The Driving Force

Muscles provide the power and control for hand movements. While many muscles controlling the hand originate in the forearm, their tendons extend into the hand, facilitating fine motor control. Key muscle groups include:

- Thenar Muscles: Located at the base of the thumb, these muscles control thumb movements, including opposition, which enables grasping.

- Hypothenar Muscles: Situated on the ulnar side of the hand, these muscles control the little finger’s movements.

- Interossei Muscles: Located between the metacarpals, these muscles contribute to finger abduction and adduction.

- Lumbrical Muscles: These muscles flex the MCP joints and extend the IP joints, contributing to precise finger movements.

Tendons and Ligaments: Support and Stability

Tendons, strong cords of connective tissue, transmit the force generated by muscles to the bones, creating movement. Ligaments, tough bands of tissue, connect bones to bones, providing stability to the joints and preventing excessive movement. This coordinated action ensures both strength and flexibility. Collateral ligaments stabilize the sides of the finger joints, while the volar plate prevents hyperextension.

Nerves: Communication and Control

Nerves transmit signals between the brain and the hand, controlling both motor function and sensory perception. Key nerves include:

- Median Nerve: Supplies sensation to the thumb, index, middle, and part of the ring finger, and controls some thenar muscles. Carpal tunnel syndrome arises from compression of this nerve.

- Ulnar Nerve: Provides sensation to the little finger and part of the ring finger, and controls some hand muscles.

- Radial Nerve: Supplies sensation to the back of the hand and controls wrist and finger extension.

Blood Vessels: Nourishment and Healing

The radial and ulnar arteries are the primary blood vessels supplying the hand. They form a network of smaller vessels that deliver oxygen and nutrients to the hand’s tissues and remove waste products. A robust blood supply is essential for maintaining hand health, promoting healing, and supporting optimal function.

Clinical Significance: Hand Injuries and Conditions

Understanding hand anatomy is crucial for diagnosing and treating various hand injuries and conditions:

- Fractures: Breaks in the bones of the hand or wrist.

- Sprains: Injuries to ligaments, often caused by excessive stretching or tearing.

- Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: Compression of the median nerve in the wrist, leading to pain, numbness, and tingling.

- Arthritis: Joint inflammation causing pain, stiffness, and limited range of motion.

- Tendonitis: Inflammation of tendons, often caused by overuse or repetitive strain.

- Dupuytren’s Contracture: Thickening and shortening of tissue in the palm, causing the fingers to curl inward.

Knowledge of hand anatomy is essential for effective treatment and rehabilitation of these and other conditions.

- Unlock Elemental 2 Secrets: Actionable Insights Now - April 2, 2025

- Lot’s Wife’s Name: Unveiling the Mystery of Sodom’s Fall - April 2, 2025

- Photocell Sensors: A Complete Guide for Selection and Implementation - April 2, 2025