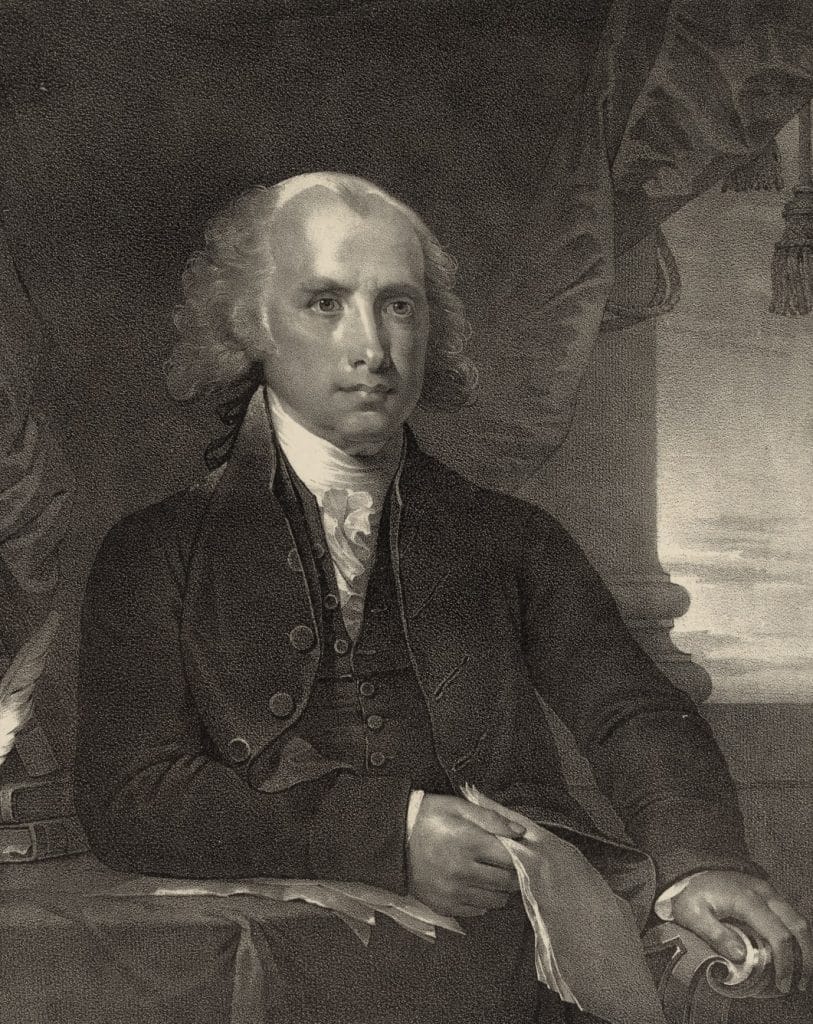

James Madison, a key architect of the United States Constitution, harbored a deep fear of how groups with shared interests, which he termed “factions,” could undermine a healthy democracy. His anxieties, vividly articulated in Federalist No. 10, continue to resonate in today’s politically charged landscape.

Unpacking Madison’s Fear of Factions

Imagine it’s the 1780s. The United States, newly free from British rule, faces the daunting task of building a government from scratch. James Madison, though a champion of democracy, recognized its potential pitfalls. His biggest concern? Factions.

Madison’s concept of factions extended beyond political parties. He envisioned them as any group, united by a common interest, that prioritizes its own agenda over the well-being of the whole. This could be a group advocating for specific economic policies, a religious group seeking to impose its beliefs, or even a social movement pushing for radical change.

Why did this worry him? Madison believed that factions, especially those representing the majority, could trample on individual rights and the interests of the minority. This “tyranny of the majority,” as he called it, could lead to instability, injustice, and ultimately, the erosion of democratic values.

The Dangers of Faction According to Madison

Madison outlined several key dangers that factions posed to a fledgling nation:

- Tyranny of the Majority: Madison feared that a majority faction could exploit the mechanisms of democracy to suppress the rights of minorities and impose its will on the entire nation. Imagine, for example, a scenario where a majority faction passes laws that discriminate against a particular religious group or silence dissenting voices.

- Instability and Gridlock: He envisioned a political system bogged down by constant conflict between competing factions, each vying for power and influence. This gridlock, he argued, would prevent effective governance and erode public trust in the government’s ability to address critical issues.

- Undermining the Common Good: Madison believed that factions, by their very nature, prioritize their own narrow interests over the well-being of society. This self-serving behavior, he argued, could lead to policies that benefit the few at the expense of the many, ultimately harming the nation as a whole.

Why Pure Democracy Couldn’t Solve the Problem

Madison believed that pure democracies, where citizens vote directly on every issue, were particularly vulnerable to the dangers of factions. In such systems, he argued, the majority could easily overpower the minority, and passions could sway public opinion more easily than reason or logic.

He pointed to the example of ancient Athens, where direct democracy often led to instability and the persecution of individuals or groups who dared to challenge the prevailing views. Madison concluded that a pure democracy, while seemingly fair on the surface, lacked the necessary safeguards to protect individual rights and ensure stable governance in a society divided by factions.

Madison’s Solution: A Large Republic

Madison’s solution to the problem of factions was not to eliminate them entirely—he recognized that this was impossible in a free society where individuals are bound to hold different views and interests. Instead, he proposed controlling their negative effects through a system of representative government within a large republic.

Here’s how he envisioned it working:

- Representation as a Filter: Instead of citizens voting directly on issues, they would elect representatives to make decisions on their behalf. These representatives, Madison argued, would be more likely to consider the common good and less susceptible to the whims of passionate factions.

- The Power of a Large Republic: A large republic, with its greater diversity of interests and opinions, would inherently make it harder for any single faction to gain a dominant majority. This diversity, he believed, would necessitate compromise and moderation.

- Checks and Balances: Coupled with the concept of a large republic was the idea of dividing governmental power among different branches—legislative, executive, and judicial—each with its own distinct powers and responsibilities. This system of checks and balances, as articulated in Federalist No. 51, aimed to prevent any single branch from accumulating too much power and becoming tyrannical.

Madison’s Enduring Legacy

Madison’s concerns about factions remain strikingly relevant today. In our current political climate, characterized by hyper-partisanship, political polarization, and the rapid spread of information (and misinformation) online, it’s easy to see echoes of the dangers he warned about centuries ago.

While the United States is not immune to the influence of factions, Madison’s framework continues to shape how we understand and address these challenges. The systems of representative government, checks and balances, and the ongoing pursuit of a “more perfect union” all stand as testaments to his enduring legacy.

Have you ever wondered why did the Schlieffen plan fail? The Schlieffen Plan, much like the political landscape Madison sought to navigate, illustrates the complexities of power struggles and unforeseen consequences.

Beyond Federalist No. 10: Exploring the Depths of Madisonian Thought

To truly understand the nuances of Madison’s fear of factions, it’s crucial to delve deeper into his ideas and their historical context:

- The Influence of History: Madison’s thinking was deeply shaped by his study of history, particularly the rise and fall of ancient republics. He drew lessons from the Athenian democracy, which, despite its intellectual and cultural achievements, was often plagued by instability and eventually succumbed to tyranny.

- Economic Factors: While often overshadowed by his focus on human nature, Madison also recognized the role of economic inequality in fueling factionalism. He understood that disparities in wealth could lead to social unrest and create divisions between the rich and the poor. This understanding is evident in his support for a system of checks and balances that would prevent any one economic interest from gaining too much power.

- The Role of Education: Madison believed that an educated citizenry was essential for a healthy republic. He argued that education could help mitigate the dangers of factions by fostering critical thinking skills, promoting tolerance and understanding, and encouraging citizens to think beyond their own narrow interests.

Madison’s Complex Legacy: A Balancing Act

Madison’s ideas continue to be debated and reinterpreted today. While his warnings about the dangers of factions remain relevant, some critics argue that his emphasis on controlling their effects may have inadvertently contributed to the very gridlock he feared.

Others point out that his vision of a republic, while designed to protect individual rights, was also shaped by the realities of his time, including the institution of slavery. Understanding these complexities is crucial for appreciating the full scope of Madison’s legacy and its impact on American democracy.

During World War II, the United States carried out numerous military operations in the Pacific theater. One of the most significant of these operations was the invasion of Okinawa. This historical event, though vastly different in nature, underscores the enduring human capacity for conflict and the importance of understanding its root causes—a theme central to Madison’s work.

Continuing the Conversation: Factions in the 21st Century

As we grapple with the challenges of a rapidly changing world, it’s more important than ever to engage with Madison’s ideas and consider their implications for the future of democracy:

- The Role of Social Media: How has the rise of social media, with its echo chambers and potential to amplify divisive rhetoric, affected the dynamics of factionalism? Does it exacerbate the dangers Madison foresaw, or does it offer new avenues for dialogue and understanding?

- Political Polarization: What steps can be taken to address the growing political polarization in the United States and other democracies around the world? Can Madison’s framework provide guidance, or do we need new solutions for a new era?

- The Future of Democracy: As technology advances and globalization continues to connect people across borders, how can we ensure that democratic values are upheld and protected in an increasingly complex and interconnected world?

Engaging with these questions is not just an academic exercise. It’s a vital step in safeguarding the principles of liberty, equality, and justice that underpin a thriving democracy. And as we navigate these uncharted waters, the wisdom of James Madison, a man who grappled with similar challenges centuries ago, can serve as both a guide and a cautionary tale.

It’s also worth noting that before becoming a central figure in Italian politics, Benito Mussolini had a brief stint as a teacher. This seemingly unrelated fact highlights the diverse paths individuals take and reminds us that even those who espouse dangerous ideologies can come from seemingly ordinary backgrounds.

- Crypto Quotes’ Red Flags: Avoid Costly Mistakes - June 30, 2025

- Unlock Inspirational Crypto Quotes: Future Predictions - June 30, 2025

- Famous Bitcoin Quotes: A Deep Dive into Crypto’s History - June 30, 2025