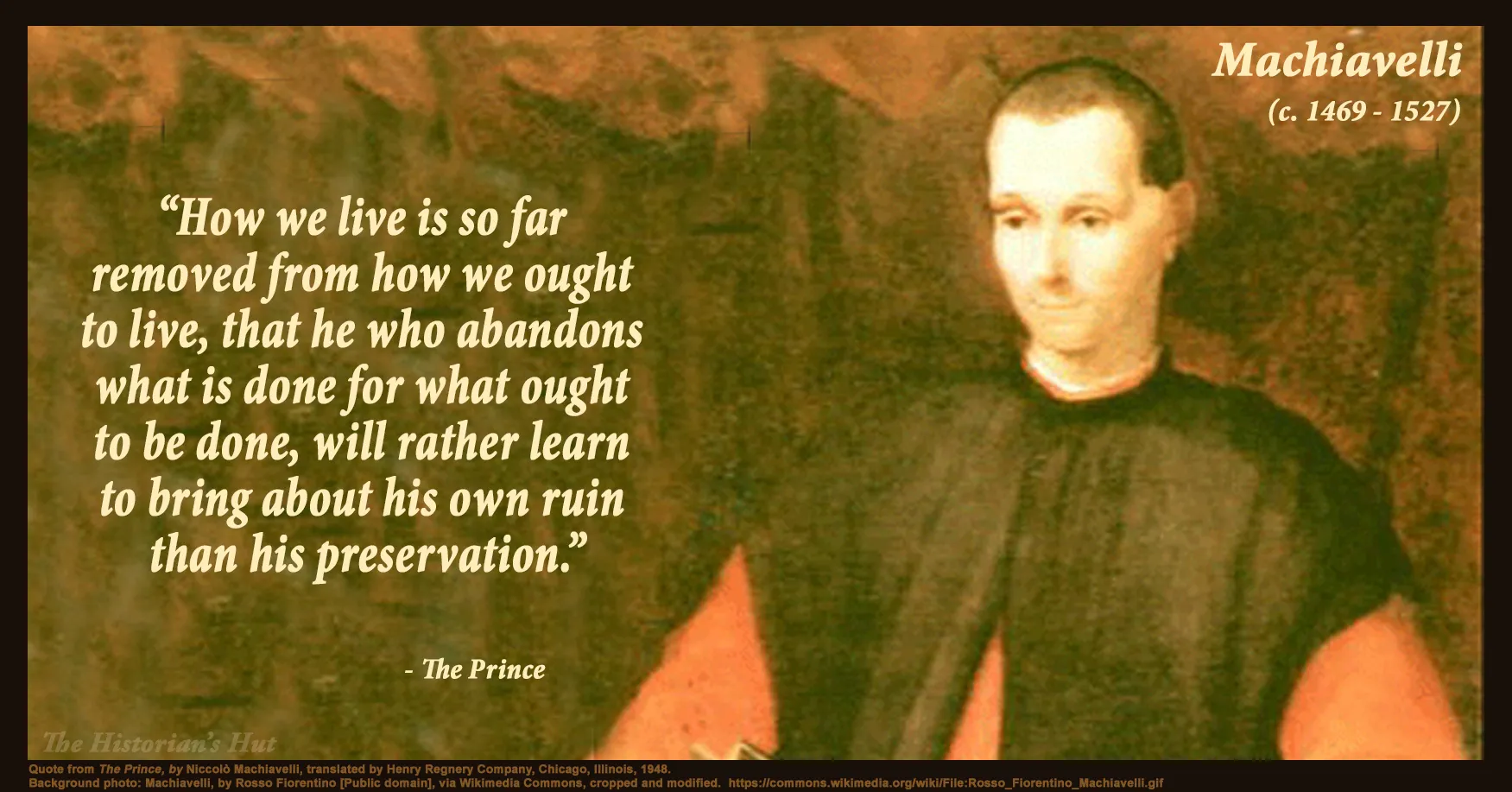

Niccolò Machiavelli, the enigmatic Florentine whose name echoes through the corridors of political thought, dared to expose a truth as uncomfortable today as it was in the heart of the Renaissance: a chasm exists between the idealized conduct we profess and the gritty realities of power. In his seminal work, “The Prince,” Machiavelli fearlessly dissects this divide, arguing that effective leadership often demands a departure from conventional morality. His insights, though controversial, offer enduring lessons on the nature of power, ambition, and the delicate dance between doing what is right and what is necessary to secure the state.

The Machiavellian Divide: Idealism vs. Political Reality

At the heart of Machiavelli’s discourse lies a stark contrast between two realms: the realm of ideals, where virtue and ethical conduct reign supreme, and the realm of political reality, a battleground ruled by self-interest, ambition, and the relentless pursuit of power. Machiavelli, ever the pragmatist, cautions against clinging to lofty ideals in the face of such stark truths. He posits that rulers who prioritize moral purity over strategic calculation risk their own downfall, observing:

“For how we live is so far removed from how we ought to live, that he who abandons what is done for what ought to be done, will rather learn to bring about his own ruin than his preservation.” – Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince

This assertion forms the bedrock of “The Prince,” a treatise often perceived as a cynical manual for tyrants. However, to categorize Machiavelli so simplistically is to overlook the nuanced understanding of human nature that underpins his work.

The Fear Factor: A Ruler’s Uncomfortable Tool

One of Machiavelli’s most enduring and unsettling maxims is the notion that, when forced to choose, it is “better to be feared than loved, if you cannot be both.” This statement, often misconstrued as an endorsement of tyrannical rule, reflects Machiavelli’s keen awareness of the ephemeral nature of love and loyalty, especially within the cutthroat arena of politics. He argues that while inspiring affection is desirable, it offers a fragile foundation for authority, easily shattered amidst adversity.

Fear, on the other hand, possesses a more enduring power. It is this potent force, Machiavelli suggests, that holds the most reliable sway over human behavior, ensuring obedience and maintaining order. However, it is crucial to note that Machiavelli does not advocate for cruelty for its own sake. His analysis emphasizes strategic calculation, urging rulers to wield fear judiciously, as a tool to secure their position and, ultimately, the well-being of the state.

Machiavelli’s Enduring Relevance: Echoes in the Modern World

Centuries after its publication, “The Prince” continues to spark debate and ignite controversy, its central tenets as relevant today as they were in the tumultuous world of Renaissance Italy. Machiavelli’s work serves as a stark reminder of the enduring tension between moral ideals and the pragmatic demands of power. His writings compel us to confront uncomfortable truths: that the pursuit of the greater good can necessitate unsavory actions, and that leadership often demands a delicate balancing act, navigating the treacherous terrain between personal ethics and the imperative to preserve the state.

From the corridors of power to the everyday decisions we face, the Machiavellian dilemma—the struggle to reconcile our ideals with the complexities of a world driven by self-interest—continues to shape our understanding of leadership, power, and the very nature of human behavior.

Dissecting Machiavelli: How We Live vs. How We “Ought” to Live

Here’s a breakdown of Machiavelli’s core argument:

1. The Core Dichotomy: Idealism vs. Realism

- Machiavelli’s Central Argument: Traditional moral frameworks, while admirable, are inadequate guides for navigating the harsh realities of political leadership.

- The Danger of Idealism: Leaders fixated on morality risk their own downfall and the destabilization of the state.

2. The Role of Fear and Love

- Love is Fleeting: Affection from citizens, while desirable, can easily erode in times of crisis.

- Fear is Enduring: A more reliable instrument for ensuring obedience and maintaining stability.

- The Ideal Balance: While being both loved and feared is optimal, rulers should prioritize being feared when a choice must be made.

3. Morality in Politics: A Delicate Dance

- The Ends Justify the Means? Machiavelli’s work sparked centuries of debate on whether noble goals justify morally questionable actions.

What is Machiavelli’s most famous quote?

Machiavelli’s most enduring axiom is: “It is better to be feared than loved, if you cannot be both.” This statement, often misinterpreted as a celebration of tyranny, reflects Machiavelli’s understanding of human nature and the precarious nature of power.

How we live is so different from how we ought to live that he who studies what ought to be done rather than what is done will learn the way to his downfall rather than to his preservation?

In this potent statement, Machiavelli highlights the chasm between our ideals and the often-unpleasant realities of human behavior. He admonishes leaders to concern themselves not with how people should act, but with how they do act, acknowledging the role of self-interest and ambition in shaping political life.

How one lives is so far distant from how one ought to live?

This question, posed by Machiavelli, encapsulates the enduring human struggle to reconcile our moral aspirations with the often-messy realities of existence. Machiavelli suggests that this disconnect is particularly pronounced in the realm of politics, where the pursuit and preservation of power frequently necessitate difficult, and often ethically ambiguous, choices.

What was Machiavelli’s main message?

Machiavelli’s central argument centers on the need for pragmatism in leadership. He argues that effective rulers must be willing to set aside conventional morality when necessary to secure the state and ensure its survival. His work emphasizes the importance of understanding and adapting to the realities of human nature, even if those realities conflict with our loftier ideals.

- William Backhouse Astor Jr.

- Henry of Bolingbroke

- Clyde Barrow

- Gustavus Adolphus Christian Groups

- Helen Herron Taft

- Haudensaunee: The Good Mind

- Rutherford B. Hayes $1 Coin

- Stephen Hawking

- Unlock Water’s Symbolism: A Cross-Cultural Exploration - April 20, 2025

- Identify Black and White Snakes: Venomous or Harmless? - April 20, 2025

- Unlocking Potential: Origins High School’s NYC Story - April 20, 2025

3 thoughts on “Machiavelli’s Timeless Dilemma: Navigating the Divide Between How We Live and How We Ought to Live”

Comments are closed.