How do we learn? Is it a solitary journey of discovery, or are we shaped by the world around us, by the people we interact with, by the culture we inhabit? Lev Vygotsky, a pioneering psychologist, argued for the latter. This article delves into the life and work of Lev Vygotsky, exploring his groundbreaking sociocultural theory and its lasting impact on our understanding of child development. We’ll unpack key concepts like the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), scaffolding, and the role of language and culture in shaping our minds.

The Architect of Sociocultural Theory

Early Life and Intellectual Journey

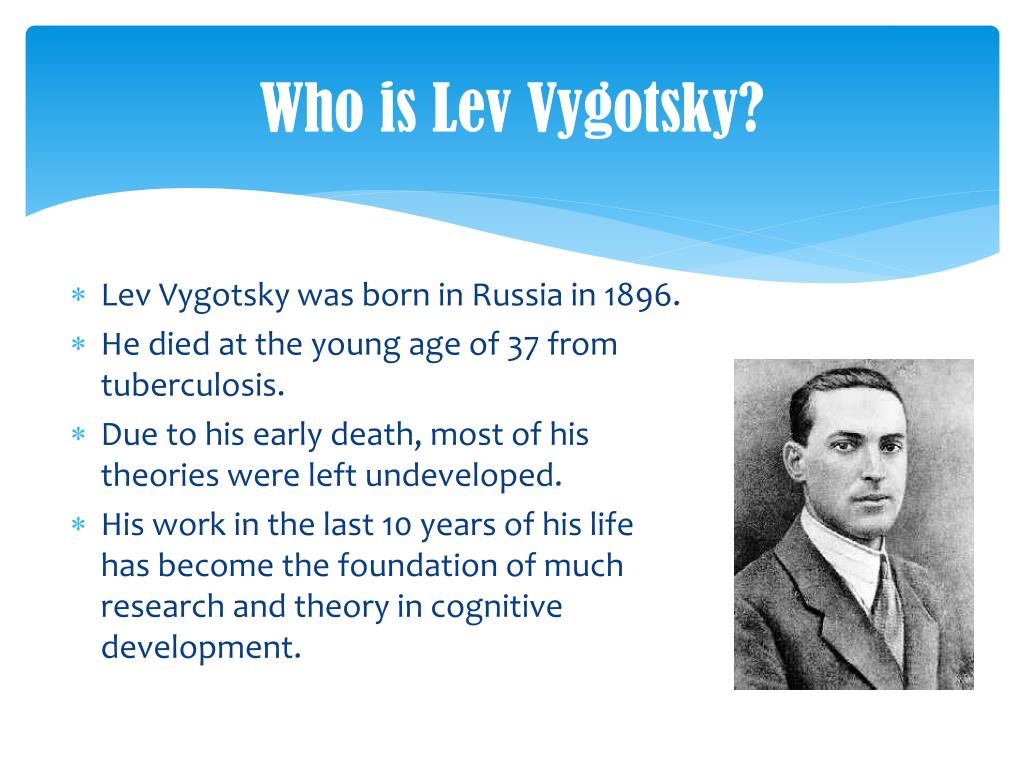

Born Lev Simkhovich Vygodsky on November 17, 1896, in Orsha, Belarus (then part of the Russian Empire), Vygotsky’s name evolved over time, likely due to evolving social and political contexts, to Lev Semyonovich Vygotsky. While the precise reasons for these changes remain unclear, his intellectual journey was one of remarkable clarity and impact. He pursued studies in law, philosophy, and history at Moscow State University, graduating in 1917, a tumultuous period in Russian history. This backdrop of social upheaval likely influenced his developing interest in the intersection of individual development and societal forces. He later pursued studies in psychology at the Shanyavsky Moscow People’s University which was established by a philanthropist and encouraged studies across a multitude of subjects. His diverse academic background provided a unique lens through which he would later examine the complexities of human learning and development.

After graduation, Vygotsky embarked on a multifaceted career, teaching literature, aesthetics, and psychology in various institutions. From 1922 to 1924, he organized and worked in a psychological laboratory at Gomel Pedagogical College, focusing on the psychology of art and education—areas that would become central to his later theoretical formulations. A pivotal moment occurred in January 1924, when he met Alexander Luria at the II Psychoneurological Congress. This encounter sparked a fruitful collaboration that significantly shaped the direction of Vygotsky’s research and contributed to the development of cultural-historical psychology. The collaboration with Luria provided mutual intellectual inspiration and support. Vygotsky also worked with Alexei Leontiev, and together these three are considered the founders of the Vygotskian school of cultural-historical psychology and activity theory. Check out Menachem Meyerson and Paulina Longworth Sturm for other influential figures of the time.

Vygotsky’s Core Ideas: A Social Lens on Learning

Vygotsky challenged prevailing psychological theories that emphasized individual, stage-based development, exemplified by the work of Jean Piaget. Instead, he posited that learning is inherently a social process, driven by interactions with others and deeply embedded within a specific cultural context. This perspective became the bedrock of his sociocultural theory, a framework that continues to resonate in educational practices today. Unlike Piaget’s emphasis on internal cognitive structures, Vygotsky viewed the external social world as the primary engine of cognitive growth. He saw development not as a solitary journey but as a collaborative enterprise, where knowledge is co-constructed through interactions with more knowledgeable others.

The Zone of Proximal Development: Where Learning Flourishes

One of Vygotsky’s most enduring contributions is the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). This concept captures the dynamic space between what a learner can do independently and what they can achieve with guidance and support. Imagine a child learning to ride a bicycle. They can’t quite balance and pedal on their own, but with a parent holding onto the seat, offering encouragement and occasional assistance, they can experience the feeling of riding. That space between their current ability and their potential, bridged by the parent’s support, is the ZPD.

The ZPD is not a static entity; it expands as the learner gains proficiency. As the child becomes more confident on the bicycle, the parent gradually reduces support, letting go for longer periods until the child can ride independently. This illustrates the dynamic nature of the ZPD and the importance of scaffolding, a concept we’ll explore in detail later. The ZPD highlights the potential for growth inherent in every learner, suggesting that with the right support, individuals can surpass their current limitations and reach new levels of understanding.

The Guiding Hand: The More Knowledgeable Other (MKO)

Central to Vygotsky’s theory is the role of the More Knowledgeable Other (MKO). This is the individual who provides guidance and support within the learner’s ZPD. The MKO can be anyone with greater expertise than the learner, including teachers, parents, mentors, peers, or even technology. In the bicycle example, the parent acts as the MKO, providing the necessary scaffolding to help the child learn. The MKO doesn’t simply tell the learner what to do; they facilitate the learning process by offering hints, asking questions, modeling behavior, and providing encouragement. This interactive process helps learners internalize new knowledge and skills, gradually moving them towards independence. The MKO’s expertise helps bridge the gap between the learner’s current abilities and the desired learning outcomes.

Scaffolding: Building a Bridge to Independence

Scaffolding, a core component of Vygotsky’s theory, describes the process of providing temporary, tailored support to a learner within their ZPD. This support is strategically designed to help the learner master tasks they couldn’t manage independently. Like the scaffolding used in constructing a building, this support is gradually withdrawn as the learner gains competence, eventually leading to independent performance. Scaffolding can take various forms, including:

- Modeling: Demonstrating the skill or process, providing a concrete example for the learner to follow.

- Think-Alouds: Verbalizing the thought processes involved in a task, making the learner aware of the underlying strategies and reasoning.

- Questioning: Posing strategic questions to guide the learner’s exploration and discovery.

- Breaking Down Tasks: Dividing complex tasks into smaller, more manageable steps.

- Providing Feedback: Offering constructive criticism and positive reinforcement to shape the learner’s progress.

Language: The Tool of Thought

Vygotsky viewed language not merely as a means of communication but as a powerful tool for shaping thought itself. He argued that language acquisition is not simply a matter of learning words and grammar; it’s a transformative process that shapes our cognitive abilities. He proposed a developmental progression of language:

- Social Speech: Used for communication with others.

- Private Speech: Self-directed speech used to guide actions and problem-solving. Often audible, particularly in children.

- Inner Speech: Internalized, silent self-talk that becomes the language of thought.

This internalization of language is central to Vygotsky’s theory. He believed that inner speech develops from social speech, gradually becoming a tool for planning, self-regulation, and problem-solving. It’s the internal dialogue that allows us to reflect on our experiences, make sense of the world around us, and direct our own actions. This emphasis on language as a tool of thought distinguishes Vygotsky’s approach from other developmental theories and highlights the profound impact of social interaction on cognitive development.

Culture’s Imprint on Cognition

Vygotsky recognized the profound influence of culture on cognitive development. He argued that cultural tools, including language, symbols, writing systems, and technology, shape how we think, solve problems, and interact with the world. These tools are passed down through generations, becoming integral to our learning processes and shaping our understanding of the world. Different cultures provide different sets of tools, leading to variations in cognitive styles and approaches to problem-solving. This emphasis on the cultural context of learning underscores the importance of considering cultural diversity in educational practices.

Vygotsky vs. Piaget: A Tale of Two Perspectives

While both Lev Vygotsky and Jean Piaget were giants in the field of developmental psychology, their theories offer distinct perspectives on how children learn and grow. Here’s a comparison:

| Feature | Piaget | Vygotsky |

|---|---|---|

| Emphasis | Individual cognitive development | Social and cultural influences |

| Driving Force | Biological maturation and self-discovery | Social interaction and cultural tools |

| Stages | Universal, invariant stages | Continuous development, no fixed stages |

| Role of Language | Reflects cognitive development | Shapes cognitive development |

| Key Concepts | Schema, assimilation, accommodation | ZPD, Scaffolding, MKO |

It’s important to note that these theories are not mutually exclusive. They offer complementary insights into the complex interplay of individual and social factors that contribute to cognitive development. While Piaget focused on the internal cognitive structures that allow children to make sense of the world, Vygotsky highlighted the external social and cultural influences that shape these structures.

A Legacy Rediscovered and Reimagined

Vygotsky’s life was tragically cut short by tuberculosis in 1934 at the age of 37. His groundbreaking work, initially suppressed in the Soviet Union for decades, gained international recognition in the latter half of the 20th century. Today, his ideas continue to inspire educators and researchers, informing best practices in teaching and learning.

Vygotsky in the Digital Age

Vygotsky’s theories are perhaps even more relevant today in our increasingly interconnected digital world. Online communities, tutorials, and collaborative platforms can serve as MKOs, expanding the opportunities for learning and growth beyond traditional classroom settings. The internet, a vast repository of information and expertise, becomes a global ZPD, connecting learners with resources and mentors from around the world. This digital expansion of the learning landscape presents both opportunities and challenges, inviting further exploration into how Vygotsky’s principles can be effectively applied in the digital age.

Ongoing Research and Open Questions

While Vygotsky’s work has profoundly influenced our understanding of learning and development, it’s important to acknowledge ongoing research and areas of continued inquiry. Some researchers question the universality of his findings, suggesting that cultural variations may influence the applicability of his theory. Others explore the intricate interplay between individual factors, like motivation and learning styles, and the social and cultural contexts Vygotsky emphasized. These ongoing inquiries enrich our understanding of his legacy and ensure its continued relevance in the ever-evolving field of cognitive science. The future may hold new insights into the complexities of social learning. His work, however, remains a cornerstone of modern educational psychology, reminding us of the powerful role of social interaction and cultural context in unlocking human potential.

- Unlocking Francis Alexander Shields’ Finance Empire: A Comprehensive Biography - July 12, 2025

- Unveiling Francis Alexander Shields: A Business Legacy - July 12, 2025

- Francis Alexander Shields’ Business Career: A Comprehensive Overview - July 12, 2025