This guide provides a comprehensive overview of lactose-fermenting Gram-negative rods, their identification, clinical significance, and the ongoing research that shapes our understanding of these microorganisms.

Understanding Gram-Negative Rods

Gram-negative bacteria, identified by their pink appearance in the Gram stain test, possess a unique cell wall structure. This structure, with a thin peptidoglycan layer and an outer membrane containing lipopolysaccharide (LPS), contributes to their resilience and pathogenicity. Want to see how nephron is labeled? Explore the labeling of the nephron by clicking the given link! labeling nephron

What Makes a Rod Lactose-Fermenting?

Lactose fermentation is a key metabolic process where bacteria use lactose, a sugar found in milk, as an energy source. This process, facilitated by the enzyme β-galactosidase (lactase), produces lactic acid and sometimes gas as byproducts. The ability to ferment lactose serves as a crucial biochemical test for bacterial identification, especially within the Enterobacteriaceae family.

The Enterobacteriaceae Family: A Closer Look

The Enterobacteriaceae family comprises a diverse group of Gram-negative rods residing in the intestinal tract of humans and animals, as well as in environments like soil and water. They are facultative anaerobes, meaning they can thrive with or without oxygen, and play a complex role in both health and disease. Many are essential for digestion, while others are opportunistic pathogens, causing infections under specific conditions.

Lactose Fermenters within Enterobacteriaceae

Rapid Lactose Fermenters: These bacteria quickly metabolize lactose, producing a rapid color change on differential media like MacConkey agar. This group includes:

- Escherichia coli (E. coli): A common gut inhabitant, some strains of which can cause infections ranging from UTIs to more serious illnesses.

- Klebsiella spp. (e.g., Klebsiella pneumoniae): Can cause pneumonia, UTIs, and bloodstream infections.

- Enterobacter spp. (e.g., Enterobacter cloacae): Opportunistic pathogens causing various infections, particularly in individuals with weakened immune systems.

Slow Lactose Fermenters: These bacteria ferment lactose more gradually:

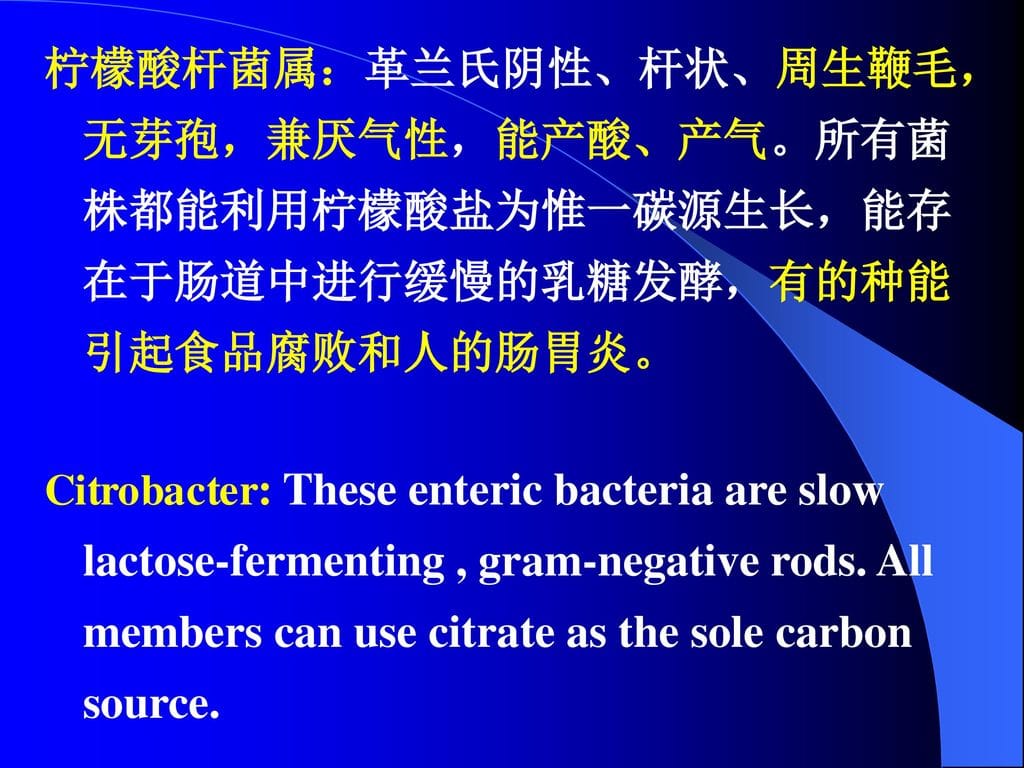

- Citrobacter spp.: Can cause UTIs, respiratory infections, and other infections. Their slow lactose fermentation can sometimes complicate initial identification, requiring additional testing. This nuance highlights that lactose fermentation is just one piece of the identification puzzle and that multiple tests contribute to a complete picture.

Non-Lactose Fermenters within Enterobacteriaceae

Not all members of the Enterobacteriaceae family ferment lactose. These non-fermenters include:

- Salmonella spp.: Causes food poisoning and typhoid fever.

- Shigella spp.: Causes dysentery.

- Proteus spp.: Can cause UTIs and wound infections.

Identifying Gram-Negative Rods: Beyond Lactose Fermentation

While lactose fermentation is a valuable diagnostic tool, other tests are essential for accurate bacterial identification. These include:

- Oxidase Test: Differentiates bacteria based on their ability to produce the enzyme cytochrome c oxidase. Most Enterobacteriaceae are oxidase-negative, while Pseudomonas, another common Gram-negative rod, is oxidase-positive.

- Nitrate Reduction: This test detects the ability of bacteria to convert nitrates to nitrites, a characteristic common among Enterobacteriaceae.

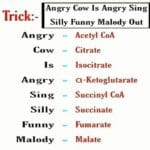

- IMViC Tests: A series of four tests (Indole, Methyl Red, Voges-Proskauer, and Citrate) that provide a more detailed biochemical profile for differentiating bacteria within Enterobacteriaceae.

- Motility: Assesses the bacteria’s ability to move, further refining identification. Most Enterobacteriaceae are motile, with Klebsiella being a notable exception.

Clinical Significance and Treatment

Lactose-fermenting Gram-negative rods are implicated in various infections, making their identification crucial for effective treatment.

- Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): E. coli is the most frequent cause, but other species like Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Citrobacter can also be involved.

- Pneumonia: Klebsiella pneumoniae is a common culprit, causing lung infections that can range from mild to severe.

- Bloodstream Infections (Sepsis): When these bacteria enter the bloodstream, they can cause sepsis, a life-threatening condition requiring immediate medical attention.

- Gastrointestinal Infections: Though less common, some lactose-fermenting Gram-negative rods can contribute to gastrointestinal issues.

Antibiotic treatment is the mainstay for these infections, but the specific antibiotic choice depends on the bacterial species and its susceptibility profile. Antibiotic resistance poses a growing challenge, making accurate identification and targeted treatment strategies essential.

Ongoing Research and Future Directions

Research continues to refine our understanding of lactose-fermenting Gram-negative rods and their interactions with human health. Current research explores:

- Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance: Understanding how resistance develops informs the development of new antibiotics and treatment strategies.

- Role of the Gut Microbiome: Research on the complex interplay between gut bacteria, including Enterobacteriaceae, and host health and disease offers potential for novel therapeutic approaches.

- Rapid Diagnostic Technologies: New molecular methods like PCR and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry promise faster and more precise bacterial identification, leading to improved patient care.

Key Points

- Lactose fermentation is a valuable tool in identifying and differentiating Gram-negative rods, especially within Enterobacteriaceae.

- E. coli, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter are common rapid lactose fermenters, while Citrobacter ferments lactose more slowly.

- Non-lactose fermenters within Enterobacteriaceae include Salmonella, Shigella, and Proteus.

- Identifying these bacteria is crucial for accurate diagnosis and appropriate antibiotic treatment of infections like UTIs, pneumonia, and bloodstream infections.

- Ongoing research addresses antibiotic resistance, the gut microbiome’s role, and the development of rapid diagnostic technologies.

This guide provides a starting point. Consulting with healthcare professionals is crucial for any health concerns, as they provide personalized guidance based on individual circumstances and the latest scientific understanding.

- Revolution Space: Disruptive Ion Propulsion Transforming Satellites - April 24, 2025

- Race Through Space: Fun Family Game for Kids - April 24, 2025

- Unlocking the Universe: reading about stars 6th grade Guide - April 24, 2025

1 thought on “Lactose-Fermenting Gram-Negative Rods: A Clinical and Diagnostic Overview”

Comments are closed.