Ever heard two notes that sound exactly the same, but are written differently? That’s the intriguing world of enharmonic equivalents. This guide unlocks their secrets, from basic definitions to advanced applications in harmony and melody.

Decoding Enharmonic Equivalents

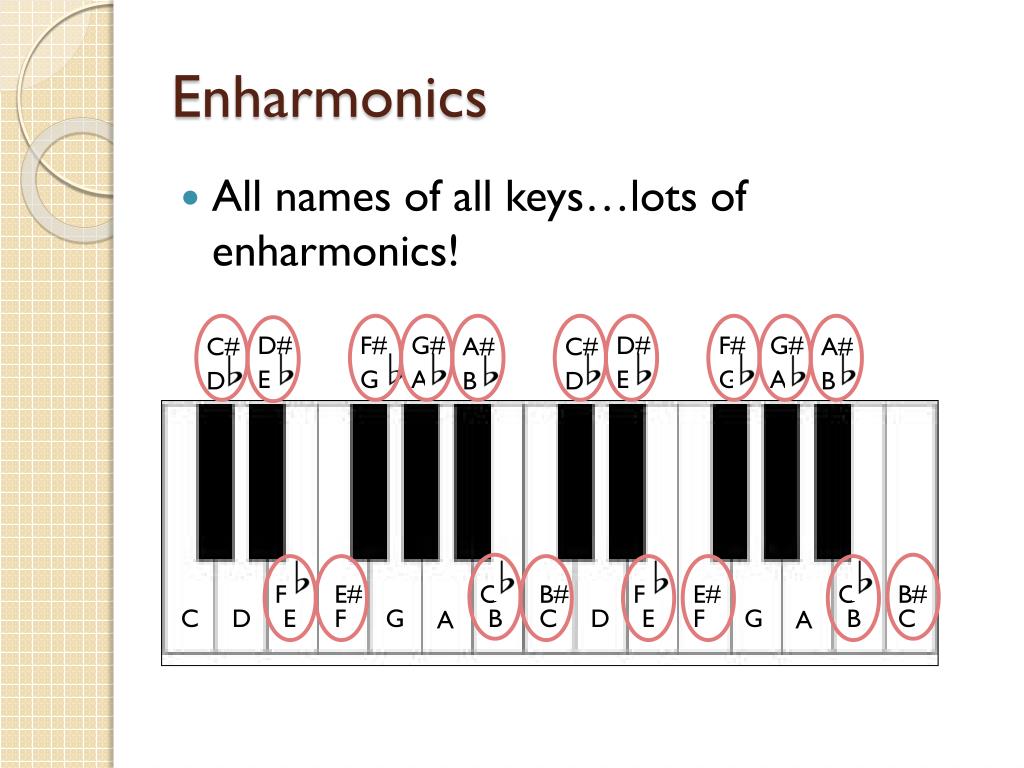

Enharmonic equivalents are simply two different names for the same pitch. Think of them as musical synonyms—like “big” and “large.” They mean the same thing, but we use them in different contexts. C sharp (C♯) and D flat (D♭) are prime examples. They occupy the same key on a piano, but their written form depends on the surrounding musical context.

What Exactly Are Enharmonic Equivalents?

Imagine playing a C♯ on a piano. Now play a D♭. Identical, right? That’s because they are enharmonic equivalents. This “musical spelling” clarifies a note’s role within a melody, chord, or key.

Why Do We Need These Musical Twins?

Western music typically uses a 12-tone equal temperament system, dividing an octave into 12 equal semitones. This system allows for enharmonic equivalents, offering flexibility in notation and simplifying complex musical passages. It’s like choosing the most efficient route on a map – sometimes going “up” (sharps) is quicker, sometimes “down” (flats) makes more sense.

Common Enharmonic Equivalents

Here are some frequent enharmonic pairs:

| Note 1 | Note 2 |

|---|---|

| C♯ | D♭ |

| D♯ | E♭ |

| F♯ | G♭ |

| G♯ | A♭ |

| A♯ | B♭ |

| B | C♭ |

| E | F♭ |

| F | E♯ |

These pairs are fundamental to understanding musical structures.

When to Use Which Note: Context is Key

Using the wrong enharmonic equivalent can make music look incorrect, even if it sounds right. In C major, you’re more likely to see C♯ than D♭. In an F minor chord, A♭ makes more sense than G♯ because it represents the minor third. Composers, like Jerome Kern in “All The Things You Are,” use enharmonic equivalents to create seamless key transitions.

Simplifying Notation: Avoiding Musical Tongue Twisters

Enharmonic spellings prevent musical “tongue twisters,” making music easier to read and play. Imagine trying to decipher music filled with double sharps and double flats! Enharmonics streamline notation, enhancing readability.

Why Enharmonic Equivalents Matter

Understanding enharmonic equivalents is crucial for any musician. It’s like understanding grammar – essential for clear communication.

- Chord Spelling and Identification: The correct enharmonic spelling reveals a chord’s identity (major, minor, diminished, etc.).

- Key Signatures: Key signatures, the sharps or flats at the beginning of a piece, guide us through the music. Enharmonics are essential for accurate interpretation.

- Interval Identification: Identifying intervals (the distance between notes) relies on understanding enharmonics. It’s crucial for analysis and performance.

- Modulation: Enharmonic equivalents allow composers to smoothly transition between keys, creating elegant and expressive musical flow.

Navigating Sharps and Flats

Finding an enharmonic equivalent involves sharpening (raising a half step) or flattening (lowering a half step) a note. Moving “up” on a keyboard usually means a sharp, while moving “down” suggests a flat.

Beyond the Basics

Mastering enharmonic equivalents empowers musicians to explore music theory, improve performance, and enhance compositional skills. They are practical tools that unlock a deeper understanding of music.

The 12-Tone System and Enharmonics

The 12-tone equal temperament system, while practical, creates a naming dilemma. Some pitches have multiple names—hence, enharmonic equivalents. These different names provide clues to a note’s function within a piece.

Enharmonic Equivalents in Action

F♯ and G♭ are enharmonic equivalents, sharing the same key on a piano. You wouldn’t write G♭ in G major; it would be like wearing a swimsuit to a formal dinner! This “musical spelling” applies to intervals (longissimus capitis), chords, and even key signatures. G♭ major (6 flats) and F♯ major (6 sharps) contain the same notes, but G♭ major is far more practical to read.

Clarity in Musical Language

Correct enharmonic spelling clarifies musical relationships, making music easier to understand. In “All the Things You Are,” the smooth transition from G# to Ab relies on understanding enharmonic equivalents.

Ongoing Research

Research continues to explore how enharmonic spellings influence musical perception. Some studies suggest subtle effects on listener experience. As music theory evolves, so might our approach to enharmonic spelling.

Five Common Enharmonic Notes

While all notes have enharmonic equivalents, some are more common. The black keys on a piano usually represent these pairs: C#/Db, D#/Eb, F#/Gb, G#/Ab, and A#/Bb. These different spellings enhance readability and prevent musical monotony within scales and chords.

Double sharps and flats introduce more equivalents. B## (double sharp) equals C, and Ebb (double flat) equals D. These may appear less frequently but are crucial in complex music.

Enharmonic equivalents affect scales (C# major uses F#, not Gb), chords (C augmented vs. Ab diminished), and key signatures (G# major vs. Ab major). Their spellings influence musical perception, similar to how context changes the meaning of spoken words.

Historically, enharmonic spellings didn’t always have the same pitch. Older tuning systems reveal a nuanced evolution of this concept.

| Note | Enharmonic Equivalent |

|---|---|

| C# | Db |

| D# | Eb |

| F# | Gb |

| G# | Ab |

| A# | Bb |

The Enharmonic Equivalent of B

B’s enharmonic equivalent is A double sharp (A𝄪). This “dressed-up twin” simplifies notation in complex musical situations, especially within keys like C# major.

The 12-tone equal temperament system enables enharmonic equivalents. Each semitone can be reached by sharps or flats, resulting in different names for the same pitch.

Enharmonic equivalents clarify key signatures (C# major vs. D♭ major), chords (C# major vs. D♭ major), and intervals (augmented fifth vs. minor sixth).

While A𝄪 is B’s primary equivalent, B double flat (B♭♭) equals A. These double sharps and flats are vital in chromatic music and maintain notational consistency.

Musical context dictates the choice between B and A𝄪. It’s about choosing the right “word” for the musical “sentence.”

| Note | Enharmonic Equivalent |

|---|---|

| C | B♯ |

| C♯/D♭ | |

| D | C𝄪 / E♭♭ |

| D♯/E♭ | |

| E | D𝄪 / F♭ |

| F | E♯ |

| F♯/G♭ | |

| G | F𝄪 / A♭♭ |

| G♯/A♭ | |

| A | G𝄪 / B♭♭ |

| A♯/B♭ | |

| B | A𝄪 / C♭ |

Ongoing research suggests that cultural and historical factors may influence our perception of enharmonic equivalents. The ischiopubic ramus plays a vital role in pelvic stability. There’s always more to discover in music!

- Revolution Space: Disruptive Ion Propulsion Transforming Satellites - April 24, 2025

- Race Through Space: Fun Family Game for Kids - April 24, 2025

- Unlocking the Universe: reading about stars 6th grade Guide - April 24, 2025