Social class cleavages represent enduring societal divisions rooted in historical power dynamics and economic inequalities, shaping political behavior and conflict. These “fault lines” within society, where different groups’ interests and opportunities often diverge, are far more nuanced than simple economic disparities. This article explores the historical origins, evolution, and modern manifestations of social class cleavages, examining their complex interplay with political behavior and societal structures.

Understanding Social Class Divisions

Social class, the hierarchical layering of individuals within a society, isn’t merely about wealth. It’s a complex interplay of power, access to resources, and perceived social standing. These disparities create cleavages, points of tension and division, that significantly impact political landscapes. While financial resources are a major factor, power dynamics—who holds influence and how that shapes opportunities—are crucial to understanding these cleavages. Just as clerestory glass in architecture allows light to permeate a building, understanding these divisions illuminates the inner workings of society.

The Historical Roots of Social Cleavage

The origins of many modern social cleavages can be traced to historical shifts. Sociologists Seymour Martin Lipset and Stein Rokkan’s influential theory posits that major historical transformations, such as the rise of nation-states and the Industrial Revolution, created deep-seated divisions that continue to resonate today. They identified four primary cleavages:

- Center vs. Periphery: This cleavage reflects the tension between centralized power and outlying regions, often manifesting as regional nationalism. A modern example is the persistent support for separatist parties in Spain.

- State vs. Church: The struggle for influence between secular and religious authority created this divide, historically exemplified by the multi-party system in the Netherlands, which featured distinct Catholic, Protestant, and secular parties until the 1970s. This cleavage likely continues to influence political discourse in many countries.

- Owner vs. Worker: This classic class conflict, central to Marxist theory, represents the tension between those who control the means of production and those who provide labor. The ongoing debate between Keynesian and liberal economic policies reflects this fundamental cleavage.

- Urban vs. Rural: Though not explicitly part of Lipset and Rokkan’s original framework, the urban-rural divide is frequently considered alongside the others, highlighting the differing needs and priorities of urban and rural populations. This cleavage is especially relevant in discussions about resource allocation and infrastructure development.

Lipset and Rokkan argued that these cleavages led to the “freezing” of party systems, with stable voter alignments persisting for generations. However, starting in the 1960s, these systems began to “unfreeze.”

The Shifting Landscape of Social Class

While social class remains highly influential, it’s no longer a simple dichotomy of rich versus poor. The concept has become more nuanced, encompassing factors like education, homeownership, and access to healthcare. These factors influence political views and voting behavior. For instance, the Brexit vote demonstrated how homeownership (homeowners vs. renters) could be a significant factor in shaping political alignments.

The traditional link between social class and voting behavior appears to be weakening. Several theories suggest possible reasons:

- Ideological Convergence: As major political parties become ideologically similar, class may become less salient in determining voting choices.

- Evolving Social Structures: With increased social mobility and the breakdown of traditional communities, class identity may become less fixed and influential.

- The Rise of Populism: Populist movements often appeal across class lines, uniting voters around shared grievances related to national identity, immigration, or cultural anxieties.

Measuring the Divide: Beyond Simple Metrics

Accurately gauging social class cleavages requires more than just income statistics. Multi-dimensional measurements, encompassing education, cultural values (cultural traits), social status, and even social networks, are necessary to capture the complexities. Two individuals with identical incomes may have vastly different opportunities and perspectives based on their backgrounds and access to resources.

Intersecting Identities: Class, Race, and Gender

Social class doesn’t exist in isolation. It intersects with other social identities like race, gender, and ethnicity, creating complex and overlapping experiences. A working-class woman, for example, probably faces different challenges and has different political priorities than a working-class man. Understanding this intersectionality is vital for comprehensive analysis.

The Future of Social Class: Ongoing Research

Globalization and technological advancements are reshaping social class cleavages. These forces can either exacerbate existing inequalities or potentially create new avenues for social mobility. Ongoing research is essential to understand these evolving dynamics and their implications for future political landscapes. For instance, automation may displace certain types of jobs, disproportionately affecting specific social groups and potentially creating new forms of social and political division.

The Four Components of Social Class

Social class is a multifaceted construct composed of four interconnected components:

- Economic: This encompasses an individual’s financial resources, including income, wealth, and assets like property. It’s not just about the amount of money but also the opportunities and security it affords.

- Social: This refers to an individual’s social connections, networks, and group memberships. These relationships can provide access to information, resources, and influence.

- Political: This component reflects an individual’s power and influence within the political system. It can involve access to decision-makers, the ability to mobilize resources for political action, and the capacity to shape public policy.

- Cultural: This encompasses an individual’s education, knowledge, skills, values, and lifestyle. These factors shape an individual’s worldview, social interactions, and ability to navigate different social environments.

These four components are intertwined. For example, economic resources can significantly influence social networks and political access. Likewise, cultural capital can impact earning potential and social standing.

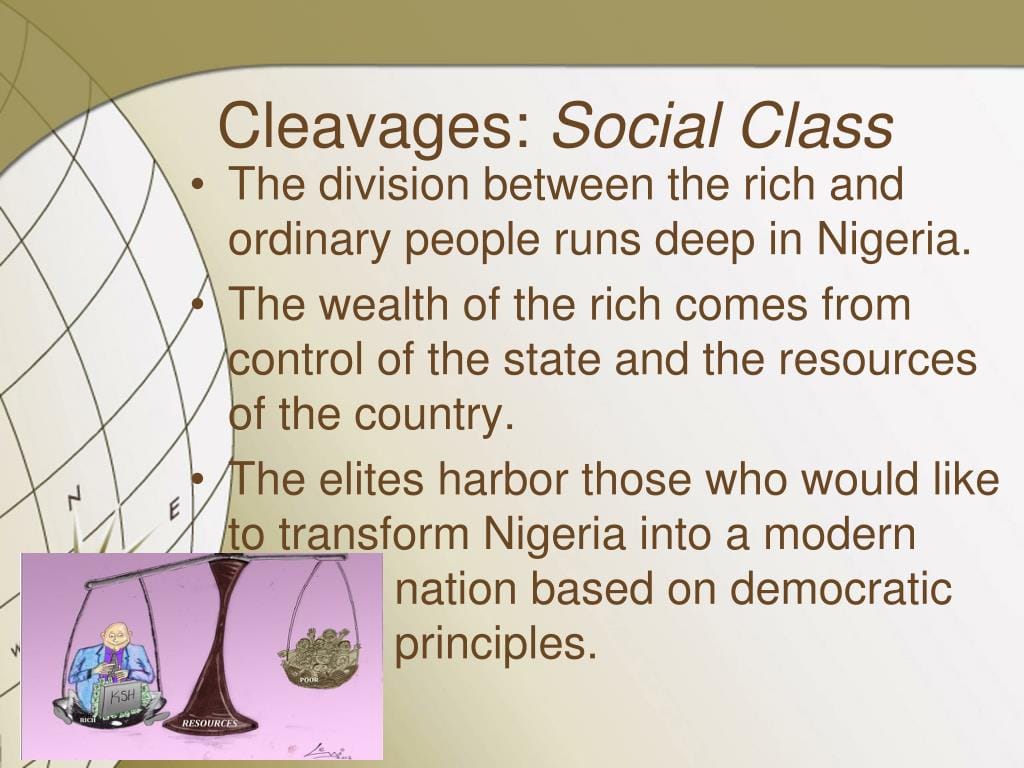

Reinforcing Cleavages: Overlapping Divides

Reinforcing cleavages occur when multiple social divisions align, intensifying political conflict and polarization. When social class aligns with other factors like ethnicity, religion, or geographic location, it can create a potent “us vs. them” dynamic. This polarization can make political compromise difficult and potentially destabilize democratic institutions.

The Organized Pattern of Social Class: A Complex Gradient

The structure of social class is no longer a simple hierarchy. While wealth and income remain important, other factors like education, occupation, social networks, and cultural capital contribute to an individual’s social standing. The contemporary model of social stratification resembles a complex gradient rather than a rigid ladder, allowing for social mobility. Individuals may move up or down this gradient throughout their lives as their circumstances change.

Several theories attempt to explain the intricate nature of social stratification. Some emphasize economic inequality, others focus on power and status, while still others highlight the role of cultural capital. Ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of how these factors interact to shape social class.

In conclusion, understanding social class cleavages is crucial for comprehending the dynamics of political behavior and societal structures. These divisions, though historically rooted, continue to evolve and reshape our world in profound ways.

- Unlock 6000+ words beginning with he: A comprehensive analysis - April 20, 2025

- Mastering -al Words: A Complete Guide - April 20, 2025

- Master Scrabble: High-Scoring BAR Words Now - April 20, 2025