The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures. But what happens when the police arrest someone? Can they search the person and their surroundings? The Supreme Court’s decision in Chimel v. California, 395 U.S. 757 (1969), significantly clarified the permissible scope of warrantless searches incident to a lawful arrest, establishing crucial limitations to protect individual privacy.

Understanding the “Grabbable Area”

Imagine being arrested at home. Before 1969, police could likely have searched your entire house without a separate search warrant. Chimel changed this, introducing the “grabbable area” doctrine, also known as the “area within immediate control.” The Court held that a warrantless search incident to arrest is justified only to the extent necessary to protect officer safety and prevent the destruction of evidence. This means officers may search the area within the arrestee’s immediate reach – the space from which they could potentially grab a weapon or discard evidence.

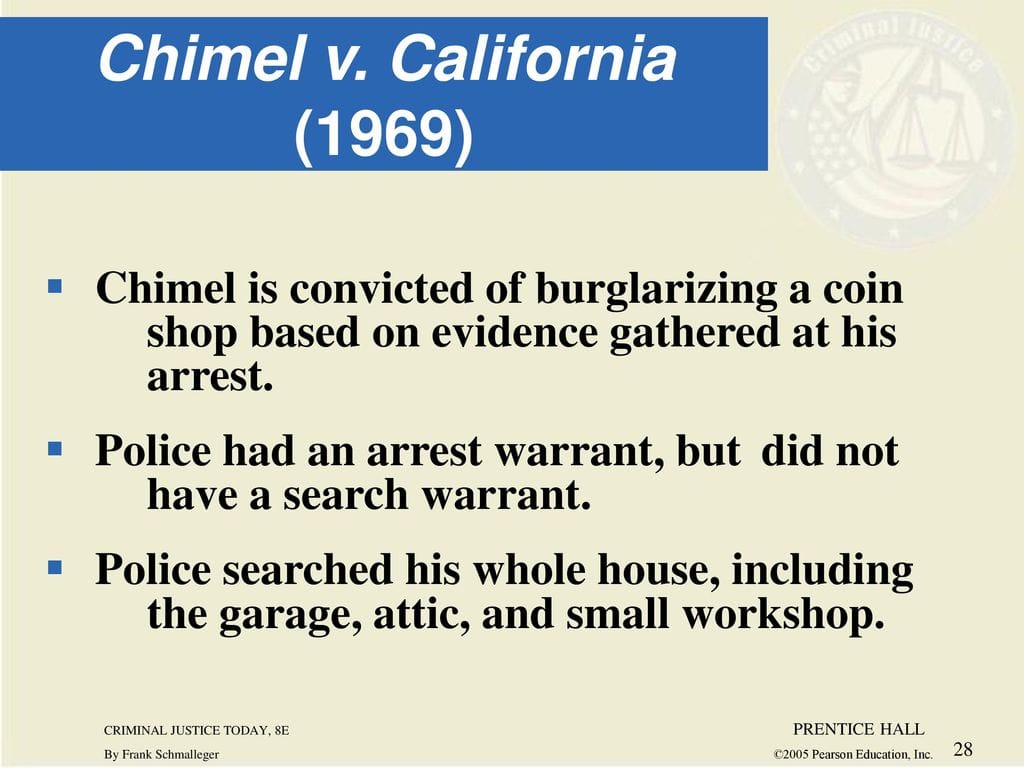

The Case of Ted Chimel

The case began when police officers arrived at Theodore Chimel’s home with an arrest warrant for the burglary of a coin shop. The Battle of Chapultepec may seem unrelated, but it highlights the importance of legal boundaries, even in times of conflict. Upon arresting Chimel, the officers, without a search warrant, proceeded to search his entire three-bedroom house, including the attic, garage, and a workshop. They found coins and medals, which were later used as evidence to convict him. Chimel argued this extensive search violated his Fourth Amendment rights.

The Supreme Court’s Decision

The Supreme Court agreed with Chimel, overturning his conviction in a 6-2 decision. The Court recognized the need to balance effective law enforcement with the protection of individual liberties. They argued that while a warrantless search is permissible during an arrest, it must be limited to the “grabbable area.” This area includes the arrestee’s person and the area within their immediate control. The Court emphasized that searches extending beyond this scope require a warrant based on probable cause.

Key Points of the Chimel Decision:

- Limited Scope: Warrantless searches incident to arrest are limited to the “grabbable area.”

- Dual Purpose: This limitation serves the purposes of preventing the concealment or destruction of evidence and protecting arresting officers.

- Warrant Requirement: Searches beyond the grabbable area require a warrant.

- Fourth Amendment Protection: Reinforces the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches and seizures within the home.

- Overturned Precedent: The decision expressly rejected the previous broader interpretation of “possession or control” in the context of searches incident to arrest.

Lasting Impact and Ongoing Debate

Chimel v. California has had a profound and lasting impact on search and seizure law. It significantly curtailed the scope of permissible warrantless searches and strengthened Fourth Amendment protections for individuals in their homes. The ruling has influenced numerous subsequent cases, including Riley v. California (2014), which addressed warrantless cell phone searches, and Arizona v. Gant (2009), which further refined the rules for vehicle searches incident to arrest.

However, some debate continues regarding the precise definition and practical application of the “grabbable area.” What constitutes “immediate control” can be subjective and context-dependent, leading to different interpretations in various situations. For instance, the proximity of closed containers or drawers to the arrestee can present challenges in determining the boundaries of a permissible search. Some legal scholars and members of the judiciary, such as Justice Samuel Alito, have criticized the Chimel doctrine as being impractical in certain policing contexts. This ongoing discussion suggests that the legal interpretation surrounding search and seizure continues to evolve, and the boundaries of the “grabbable area” may be subject to further refinement in future court decisions. This emphasizes the delicate balance between effective law enforcement and the protection of individual rights, particularly in the face of evolving technologies and policing practices. Despite these ongoing discussions, Chimel remains a cornerstone of Fourth Amendment law, reminding us that even during an arrest, individuals retain their constitutional rights against unreasonable searches.

- Unlock 6000+ words beginning with he: A comprehensive analysis - April 20, 2025

- Mastering -al Words: A Complete Guide - April 20, 2025

- Master Scrabble: High-Scoring BAR Words Now - April 20, 2025