This article delves into the landmark Supreme Court case Chimel v. California (1969), which significantly altered the landscape of search and seizure law in the United States. We’ll explore the case details, the “arm’s reach” doctrine it established, and its lasting impact on Fourth Amendment protections.

The Story of Chimel v. California

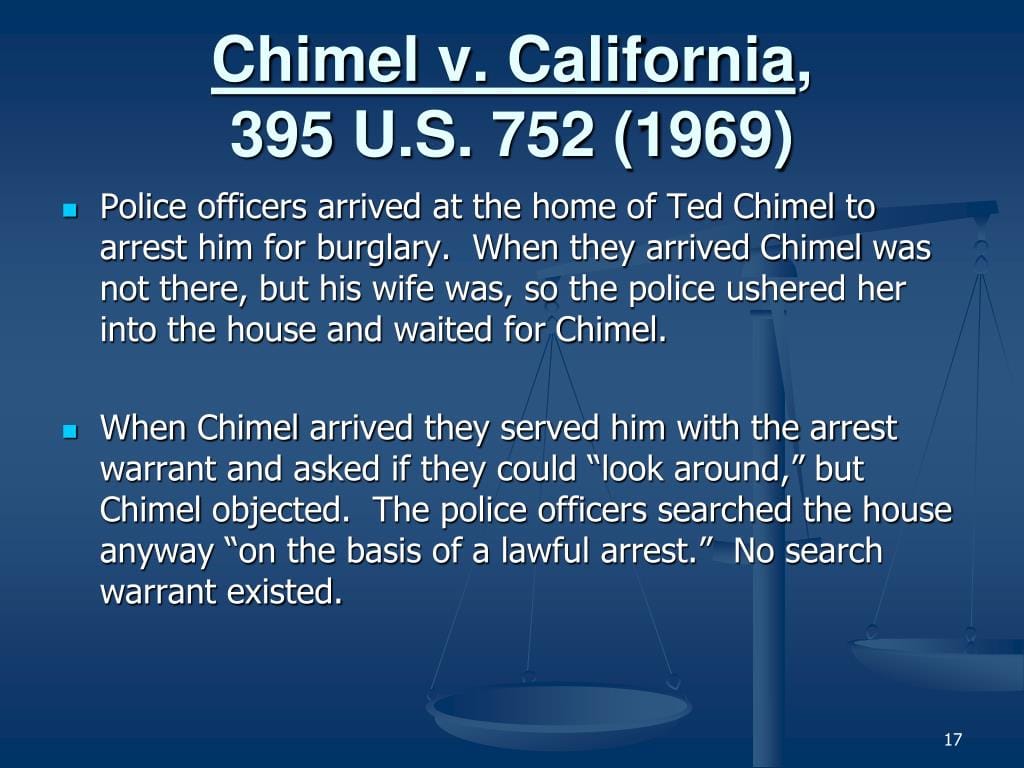

In 1969, police officers arrived at Ted Steven Chimel’s home with an arrest warrant for a coin shop burglary. Upon arresting him inside, the officers conducted an extensive search of his entire three-bedroom house, including areas well beyond his immediate reach. Chimel denied the request of officers to look around his home. The police “instructed Chimel’s wife to remove items from drawers.” They discovered incriminating evidence, including coins, medals, and tokens. Chimel argued that this broad search violated his Fourth Amendment rights protecting against unreasonable searches and seizures. His case ultimately landed before the Supreme Court.

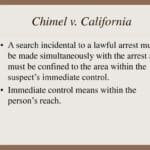

The Supreme Court’s Ruling: Birth of the “Arm’s Reach” Doctrine

The Supreme Court, in a 6-2 decision, sided with Chimel. The Court acknowledged the need for officers to search the immediate area of an arrest to ensure their safety and prevent evidence destruction. However, they argued that this search must be limited to the area within the arrestee’s immediate control—what they termed the “grabbing area” or “wingspan.” This area is often described as being within “arm’s reach.” The Court deemed the search of Chimel’s entire house an overreach of police authority. This ruling established the “arm’s reach” doctrine, formally limiting the scope of warrantless searches incident to arrest.

Understanding “Immediate Control”

The “area within immediate control” refers to the space from which an arrestee might gain possession of a weapon or destructible evidence. It’s the area within their reach, sometimes visualized as their wingspan. This concept balances officer safety with the individual’s Fourth Amendment rights. However, the exact boundaries can be open to interpretation and may vary based on the specific circumstances of the arrest, including the arrestee’s physical abilities, the layout of the surrounding area, and any obstacles present. For example, if someone is arrested at their desk, the permissible search area probably includes the desk surface and drawers within easy reach, but not files in a locked cabinet across the room. Ongoing legal discussion exists about refining these boundaries, as new technologies and scenarios constantly emerge.

Lasting Impact of Chimel

Chimel v. California significantly impacted search and seizure procedures, reinforcing Fourth Amendment protections. It became a cornerstone of Fourth Amendment law, influencing countless subsequent cases and changing police training to emphasize the limitations of warrantless searches. The ruling also sparked debate about digital searches. Should the principles of Chimel apply to cell phones? Some experts believe they should, while others argue that the vast amount of data on digital devices requires a different approach. This question remains a topic of legal and scholarly contention.

Chimel in the Digital Age: Riley v. California

The digital age presents unique challenges to the “arm’s reach” doctrine. Riley v. California (2014) addressed the search of cell phones incident to arrest, recognizing the vast amount of personal information stored on these devices. The Court placed limitations on such searches, reflecting the evolving understanding of privacy in the digital age and suggesting that Chimel‘s principles, while foundational, might require adaptation in the digital context. [https://www.lolaapp.com/admiral-byrd-diary]

Key Takeaways from Chimel v. California

- Established the “arm’s reach” doctrine, limiting warrantless searches incident to arrest.

- Reinforced Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures.

- Changed police procedure, necessitating warrants for searches beyond the arrestee’s immediate control.

- Influenced subsequent case law, shaping the interpretation of search and seizure law.

- Continues to be relevant in the digital age, sparking debate about the scope of digital privacy

Chimel v. California: Case Details and Significance

- Case Name: Chimel v. California, 395 U.S. 757 (1969)

- Court: United States Supreme Court

- Year: 1969

- Issue: Constitutionality of a warrantless search of a home incident to an arrest.

- Facts: Police arrested Ted Chimel in his home with an arrest warrant but no search warrant. They searched his entire three-bedroom house, finding evidence later used in his burglary conviction. Chimel challenged the search, claiming it violated his Fourth Amendment rights.

- Holding: The search beyond Chimel’s immediate control was deemed unconstitutional.

- Reasoning: Searches incident to arrest are limited to the “grabbing area” to protect officer safety and prevent evidence destruction. A wider search requires a warrant.

- Vote: 6-2 for Chimel

- Majority Opinion: Justice Stewart

- Dissenting Opinions: Justices Black and White

- Significance: Established the “arm’s reach” doctrine, significantly impacting police procedures and reaffirming Fourth Amendment protections.

Chimel v. California remains a critical case in Fourth Amendment jurisprudence. It provides a crucial framework for balancing law enforcement needs with individual privacy rights, though the precise limits of a permissible search can still be subject to interpretation. This ongoing discourse underscores the importance of Chimel in the legal landscape.

- Discover Long Black Pepper: Flavor & Health Benefits - April 25, 2025

- Shocking Twists: The Grownup Review: Unreliable Narration - April 25, 2025

- A Quiet Place Book vs Movie: A Deep Dive - April 25, 2025

![[Ancient Coins of India Price]: Unveiling the Value of Historical Treasures ancient-coins-of-india-price_2](https://www.lolaapp.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/ancient-coins-of-india-price_2-150x150.jpg)