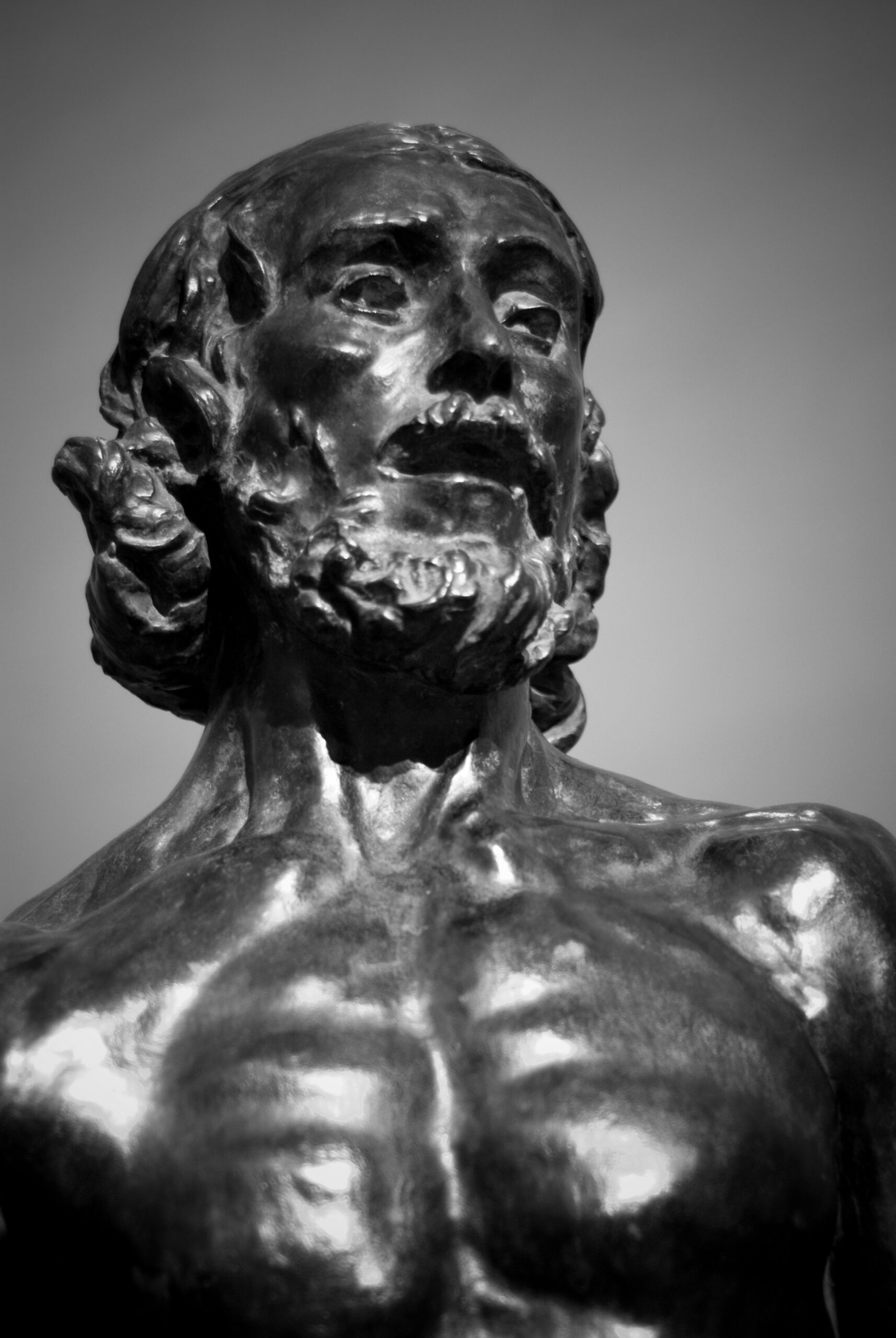

Auguste Rodin’s *The Thinker* (*Le Penseur* in French) is arguably one of the most recognizable sculptures in the world. More than just a “man thinking,” it encapsulates the complexities of human thought, resonating with viewers for over a century. This deep dive explores its rich history, artistic significance, and enduring legacy, examining its journey from a component within *The Gates of Hell* to its global recognition as a standalone masterpiece.

From The Gates of Hell to Global Icon

The Thinker (originally Le Penseur, meaning “the poet”) was initially conceived as part of Rodin’s monumental work, The Gates of Hell (1880-1917), a bronze portal inspired by Dante’s Inferno. Commissioned for a museum that was never built, the door featured numerous figures, with The Thinker, representing Dante himself, perched above the doorway, surveying the swirling depiction of hell below. [https://www.lolaapp.com/anglo-saxon-futhorc-runes]

Evolution of an Idea: Rodin’s Creative Process

Rodin didn’t simply create The Thinker in one go. The sculpture evolved over time, going through numerous iterations, with Rodin experimenting with size, pose, and the overall emotional impact. From early small-scale studies to the monumental final casts, each version reflects a step in Rodin’s creative journey, mirroring the very act of thinking the sculpture embodies. These variations suggest a continual process of refinement, hinting that Rodin was less interested in a static representation of thought and more intrigued by capturing its dynamic and evolving nature.

Decoding the Pose: A Physical Manifestation of Thought

The iconic pose—seated, nude, chin resting on fist, elbow on knee—has become synonymous with deep contemplation. But what is The Thinker actually thinking? Some believe the tension in his muscles suggests not just reflection, but an intense mental struggle, perhaps even intellectual agony. This interpretation is supported by Rodin’s choice to depict the figure with a realistic, powerful physique, rather than an idealized form. This suggests Rodin saw thinking not as a purely cerebral activity, but a whole-body experience, a visceral engagement with the world of ideas.

The Power of Scale: From Miniature to Monumental

The Thinker exists in multiple sizes, ranging from small studies to colossal casts. A bronze study, measuring a mere 31.5 cm high, offers an intimate encounter with the sculpture, while the monumental versions, towering over the viewer, create a sense of awe and grandeur. This variation in scale likely alters how we perceive the work. Does a larger Thinker inspire different emotions than a smaller one? This question invites further contemplation on how scale impacts our interpretation of art.

A Global Presence: The Thinker Around the World

The original, large-scale The Thinker, cast in 1902, resides at the Musée Rodin in Paris. However, numerous other casts are located throughout the world, each offering a unique experience. From the contemplative setting of the Rodin Garden at the North Carolina Museum of Art to the historical context provided by Ordrupgaard Museum in Denmark (which emphasizes its connection to The Gates of Hell), The Thinker prompts reflection wherever it is displayed. This global presence raises questions about the nature of art in the age of reproduction. Does the existence of multiple casts diminish the original’s aura or amplify its message by making it accessible to a wider audience?

An Enduring Legacy: Why The Thinker Still Matters

The Thinker‘s influence pervades popular culture. It has become a universal symbol of intellectual pursuit, introspection, and the human condition, appearing in everything from postcards to parodies. Its enduring appeal may stem from its ability to capture the timeless human fascination with the inner workings of the mind, the mysteries of consciousness, and our relentless quest to understand ourselves and our place in the universe.

Rodin and Rose Beuret: A Love Story Forged in Clay

Rodin and Rose Beuret’s relationship, spanning over five decades, was a complex tapestry of love, loyalty, and public scandal. Their story began in 1864 when Beuret, a young seamstress, became Rodin’s model and partner, a scandalous arrangement in 19th-century France. They shared their lives, facing social disapproval and navigating the turbulent waters of Rodin’s artistic career. Beuret was not simply a lover; she was his muse, a constant source of support, and the anchor in his often chaotic world. Their son, Auguste-Eugène, born in 1866, remained largely unacknowledged by Rodin, adding another layer of complexity to their relationship.

The question that continues to intrigue scholars and art enthusiasts alike is: why did Rodin marry Rose Beuret after 53 years, a mere two weeks before her death in 1917? Several theories exist. Was it a deathbed promise fulfilled? A final grand gesture of love and atonement? Or perhaps a pragmatic attempt to secure her financial future given societal constraints? The timing, so close to her death, and Rodin’s own declining health, suggests the possibility of a deathbed reconciliation.

Rodin’s infamous affair with Camille Claudel, his talented student and lover, further complicates the narrative. Beuret’s steadfastness through this tumultuous period underscores the depth of their bond. The interplay between these relationships offers a glimpse into the complexities of love and loyalty in the late 19th century.

The true reason for their belated marriage remains shrouded in mystery, likely lost to time. However, ongoing research and the examination of personal correspondence may one day shed more light on this enduring enigma.

Was Rodin a Catholic? A Spiritual Journey Shaped by Grief

Rodin’s relationship with Catholicism wasn’t a lifelong devotion, but rather a brief, intense period intertwined with personal tragedy. The death of his sister, Maria, in 1862 plunged him into profound grief, leading him to seek solace within the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament. This spiritual detour, however, was short-lived. Father Pierre-Julien Eymard, recognizing Rodin’s burgeoning artistic talent, encouraged him to leave the order and pursue his true calling.

While his time within the Church was brief, it likely left an indelible mark on his artistic sensibilities. Though not a practicing Catholic throughout his life, subtle echoes of this spiritual journey can arguably be discerned in his work. The emotional depth, the human vulnerability so powerfully conveyed in his sculptures, may be a reflection of his own internal struggles with faith, loss, and the search for meaning. Even The Thinker, though not explicitly religious, embodies a profound engagement with the human condition, reflecting the introspective nature of Rodin’s own spiritual exploration.

The interplay between Rodin’s brief immersion in Catholicism and his subsequent artistic expression invites further investigation. Ongoing research continues to explore the potential connections between his spiritual experiences and the themes explored within his oeuvre, offering a deeper understanding of the man and the artist.

The Rodin Economy: From Struggling Artist to Financial Powerhouse

Rodin’s financial success wasn’t solely due to artistic genius; it was also a product of shrewd business acumen and innovative practices. The Gates of Hell, though unfinished, became a goldmine. Rodin realized he could reproduce individual figures from the portal, such as The Thinker and The Kiss, creating and selling multiple editions. This strategic move transformed a seemingly failed commission into a lucrative enterprise.

His adoption of the lost-wax casting method was another financially astute decision. This technique allowed him to produce multiple bronze casts of his sculptures, satisfying increasing demand without starting from scratch. He also strategically employed numerous studio assistants, streamlining his production process and further maximizing output.

Rodin understood the importance of patronage and cultivating relationships with influential figures. Securing commissions from both wealthy individuals and the state provided a consistent income stream. His handling of a controversial public commission for a Balzac monument further demonstrates his business savvy. By repaying the commission and installing the sculpture in his own garden, Rodin protected his reputation and retained control over his work.

Perhaps his most brilliant financial move was authorizing the posthumous casting of his sculptures. This ensured a continued revenue stream for his estate, managed by the Musée Rodin, solidifying his financial legacy and supporting the preservation of his work for generations to come.

Rodin’s success raises intriguing questions about the relationship between art and commerce. Did his commercial endeavors compromise his artistic integrity? Or did his financial security grant him the freedom to pursue his artistic vision unburdened by financial constraints? Ongoing discussion surrounding this topic adds another layer of fascination to Rodin’s complex legacy.

- Unlocking Francis Alexander Shields’ Finance Empire: A Comprehensive Biography - July 12, 2025

- Unveiling Francis Alexander Shields: A Business Legacy - July 12, 2025

- Francis Alexander Shields’ Business Career: A Comprehensive Overview - July 12, 2025

1 thought on “Auguste Rodin’s Grubleren: A Deep Dive into The Thinker”

Comments are closed.