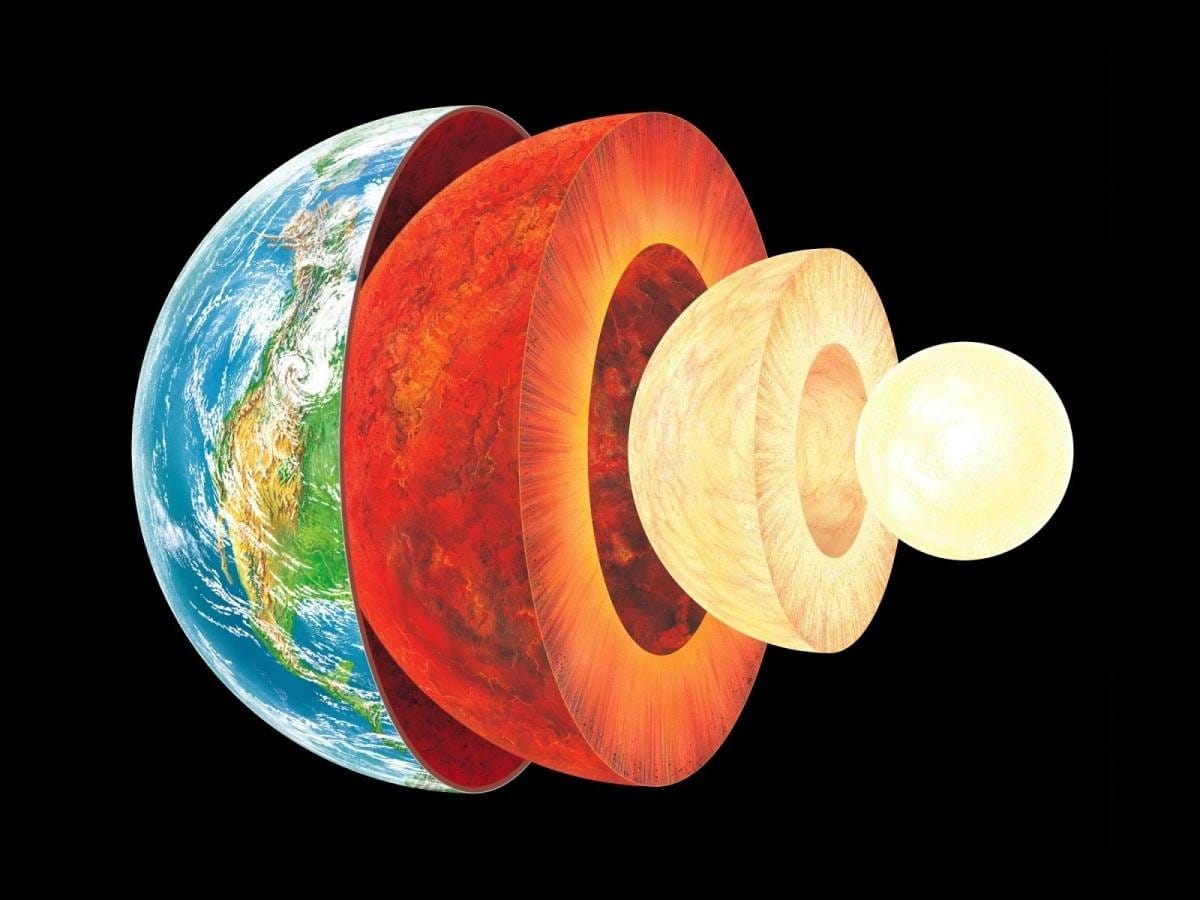

Comprising the outermost solid shell of our globe, the crust of the Earth is a quite thin layer of rock. Relative speaking, its thickness is similar that of an apple’s skin. Though it makes less than half of 1% of the mass of the earth overall, it is nonetheless essential in most natural cycles on the globe.

In certain areas the crust could be less than one kilometer thick and thicker than 80 kilometers in others. Beneath it is the mantle, a layer of silicate rock roughly 2700 kilometers thick. The mantle makes up most of the planet.

There are several varieties of rocks in the crust, mostly falling into three main groups: igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary. Still, most of those rocks started off as either granite or basalt. Underneath lies a peridotite mantle. Deeply in the mantle is the most often occurring mineral on Earth: bridgmanite.

How Are We Certain the Earth Has a Crust?

Early in the 1900s, we learned the Earth had a crust. Until then, all we knew was that, at least from astronomical observations, our planet wobbles in respect to the heavens as though it had a sizable, dense core. Then along came seismology, which introduced seismic velocity as a fresh kind of evidence from below.

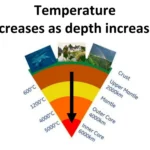

Seismic velocity gauges the speed with which earthquake waves pass through the various materials—that is, rocks—below the surface. Seismic speed inside the Earth usually rises with depth, with a few significant exceptions.

About 50 kilometers deep in the Earth, a paper by seismologist Andrija Mohorovicic revealed an abrupt change in seismic velocity — a form of discontinuity. The same way light behaves at the discontinuity between water and air, seismic waves bounce off it (reflect) and bend (refract). The acknowledged limit separating the crust from the mantle is that discontinuity known as the Mohorovicic discontinuity, or “Moho”.

Plates and “Crispes”

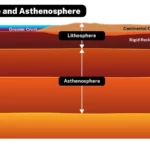

Not the same are the crust and tectonic plates. Thicker than the crust, plates comprise the crust plus the shallow mantle right under it. In scientific Latin, this hard and brittle two-layered mix is known as the lithosphere (“stony layer”). The asthenosphere (“weak layer”) of softer, more pliable mantle rock lies underneath the lithospheric plates. The asthenosphere lets the plates slink slowly over it like a raft across thick mud.

We are aware that two main types of rocks define the outer layer of the Earth: granitic and basaltic ones. Granitic rocks form the continents; basaltic rocks lay beneath the sea floor. Measuring in the lab, we find that the seismic velocities of these rock forms mirror those observed in the crust down as far as the Moho. We thus have great confidence that the Moho represents a genuine shift in rock chemistry. The Moho is not a perfect barrier since some mantle and crustal rocks can pass for each other. Still, everyone who discusses the crust—in seismological or petrological terms—finally means the same thing.

Generally speaking, then, there exist two types of crust: continental (granitic) and oceanic (basaltic).

Oceanic Crust

About sixty percent of the surface of Earth is covered in oceanic crust. Thin and youthful, oceanic crust is no more than around 20 km thick and ages no more than 180 million years. Subduction has carried everything older beneath the continents. Born at the mid-ocean ridges when plates are driven apart, oceanic crust…

Continental Crust

Covering over 40 percent of the world, continental crust is massive and ancient, on average roughly 50 km thick and about 2 billion years old. Whereas most of the continental crust is accessible to the air, practically all of the oceanic crust is submerged.

What the Crust Implies

Thin but vital, the crust is where new types of minerals and rocks are created as dry, heated rock from the deep Earth mixes with the water and oxygen of the surface. Here is also where plate-tectonic action mixes and scrambles these fresh rocks and pumps chemically active fluids into them. At last, life resides in the crust; this influences rock chemistry greatly and has own mechanisms of mineral recycling. From metal ores to deep strata of clay and stone, all of the fascinating and worthwhile variety in geology finds its place in the crust and nowhere else.

It should be mentioned that other planetary bodies have a crust besides Earth. One also exists for Venus, Mercury, Mars, the Earth’s Moon.

Though far thinner than the other layers, the crust of the Earth is shockingly dynamic and sophisticated. It is an interesting field of research since it interacts constantly with the mantle, the atmosphere, even life itself. Comprehending earthquake, volcanoes, and the creation of the landscapes defining our globe depends on an awareness of the crust.

- Unlock Water’s Symbolism: A Cross-Cultural Exploration - April 20, 2025

- Identify Black and White Snakes: Venomous or Harmless? - April 20, 2025

- Unlocking Potential: Origins High School’s NYC Story - April 20, 2025