Ayuba Suleiman Diallo’s journey embodies the complex intersection of faith, slavery, and literacy in the 18th-century Atlantic world. From Senegalese nobleman to enslaved laborer to published author, Diallo’s life defied simple categorization. His story is one of resilience, faith, and the fight against slavery, a testament to the power of the human spirit against unimaginable adversity.

Early Life and Unexpected Capture (1701-1731)

Ayuba Suleiman Diallo was born in 1701 in Bundu, Senegal, into a prominent Fulani Muslim family of clerics and merchants. His upbringing was one of privilege, steeped in religious study and the intricacies of trade. This early exposure to both spiritual and worldly matters likely shaped his worldview and provided him with a foundation that would prove invaluable in the trials to come. Crucially, Diallo was literate in Arabic, a skill that would later play a pivotal role in his remarkable journey. He likely participated in the family’s mercantile activities, including, perhaps regrettably, the trade of enslaved people, a practice that adds layers of complexity to his own later enslavement. This aspect underscores the deeply ingrained nature of slavery within the 18th-century economic and social fabric, a system that tragically entangled both victims and perpetrators.

In 1731, Diallo’s life took an abrupt and devastating turn. He was captured and sold into slavery. The circumstances of his capture remain somewhat unclear, but the result was his forced removal from his homeland and family, a traumatic experience that marked the beginning of a harrowing chapter in his life. This sudden shift from a position of privilege to one of utter powerlessness is a stark reminder of the precarious nature of freedom during this era. The vibrant world he knew – the bustling markets, the intellectual discussions, the comfort of his family – was replaced by the brutal reality of the transatlantic slave trade.

Enslavement and the Power of Literacy (1731-1733)

Transported across the Atlantic, Diallo found himself in Maryland, forced to labor on a tobacco plantation. The conditions were undoubtedly harsh, designed to strip enslaved people of their dignity and humanity. Diallo’s experience likely mirrored the suffering of countless other Africans subjected to this brutal system. The physical and psychological toll of forced labor, coupled with the constant threat of violence and the pain of separation from loved ones, must have been immense.

Amidst this despair, Diallo’s literacy in Arabic emerged as an unexpected lifeline. While Olaudah Equiano’s birthplace is a subject of ongoing scholarly debate, Diallo’s African origins are well-documented, further setting their narratives apart. His ability to read and write set him apart from other enslaved people and sparked the curiosity of those he encountered. One such encounter proved pivotal: his meeting with Thomas Bluett. Bluett, perhaps recognizing the injustice of Diallo’s situation, saw something special in the literate African. This encounter led to communication with James Oglethorpe, founder of the Georgia colony, who played a key role in securing Diallo’s freedom in 1733. Diallo’s literacy, a skill honed in his youth, had become an instrument of his liberation, a testament to the enduring power of education even under the most oppressive circumstances.

Freedom, Return, and a Complicated Legacy (1734-1773)

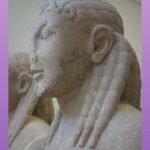

Following his emancipation, Diallo traveled to England, where he met influential figures and shared his story, likely challenging prevailing perceptions of enslaved Africans. William Hoare’s portrait of Diallo, painted during this time, captures not only his physical likeness but also his dignity and resilience. It serves as a powerful visual representation of a man who reclaimed his identity after being brutally stripped of it. This image, widely circulated, may have contributed to the growing abolitionist movement by humanizing the victims of the slave trade.

In 1734, Diallo returned to Africa, where he resumed his life as a merchant and religious leader. The emotional and psychological impact of his enslavement undoubtedly stayed with him, but he continued to live a full life until his death in 1773. His narrative, however, was not lost to time. His memoirs, Some Memoirs of the Life of Job, the Son of Solomon, the High Priest of Boonda in Africa, published shortly after his return, provide a rare and invaluable first-person account of the transatlantic slave trade. This written testimony stands as a powerful indictment of the system and a testament to his resilience.

Diallo’s legacy is complex. He was both a victim and, prior to his enslavement, likely a participant in the slave trade. This duality adds layers of nuance to his story and challenges us to confront the moral ambiguities of the time. His experience also underscores the power of literacy, faith, and human connection in the face of unimaginable hardship. By comparing Diallo’s narrative with other accounts of enslavement, such as the powerful story of Olaudah Equiano, we can gain a deeper understanding of the diverse and complex experiences of enslaved Africans, the various paths to freedom, and the enduring fight for human dignity. Learn more about the fascinating world of language and culture by exploring the inseki meaning of word. For those interested in culinary adventures, discover the secrets to perfectly popped kernels with our guide on instructions for whirley pop.

- China II Review: Delicious Food & Speedy Service - April 17, 2025

- Understand Virginia’s Flag: History & Debate - April 17, 2025

- Explore Long Island’s Map: Unique Regions & Insights - April 17, 2025