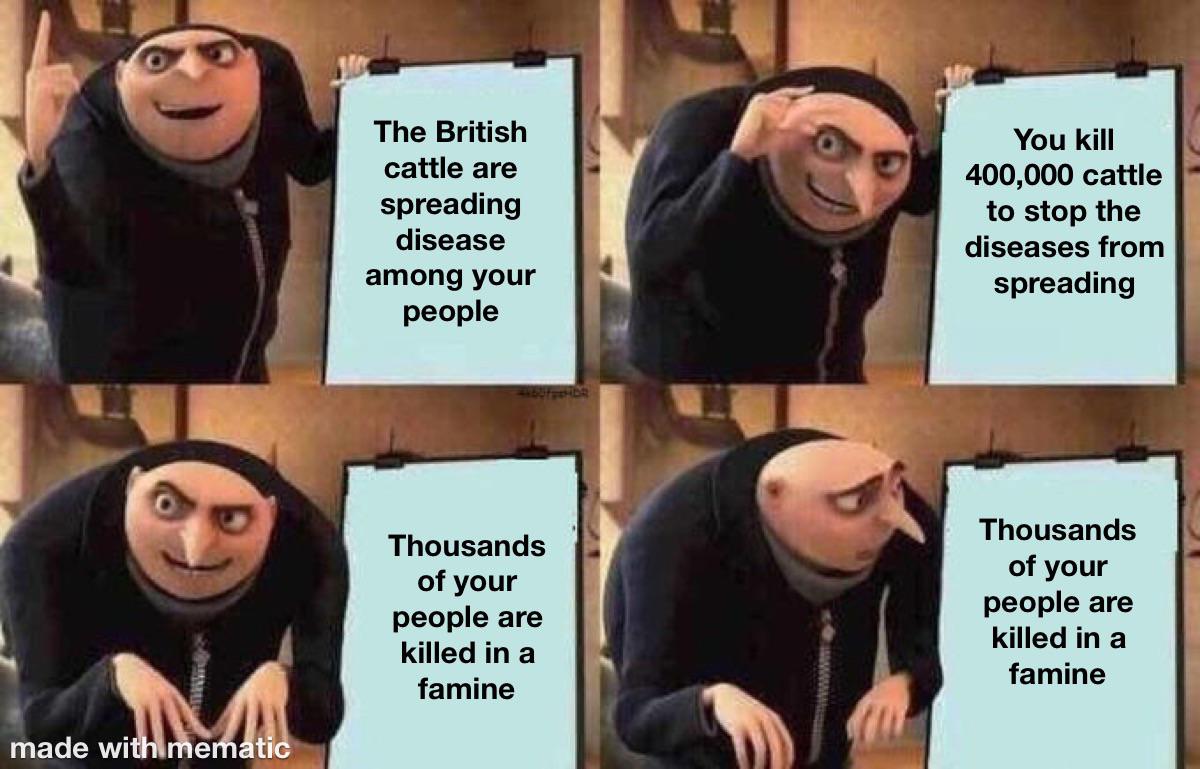

In the mid-1850s, under the looming shadow of British colonialism and amidst the ravages of cattle disease, the Xhosa people of Southern Africa faced a crisis of unimaginable proportions. Into this crucible of despair stepped a young prophetess, Nongqawuse, with a vision of deliverance. Her prophecy—slaughter your cattle, destroy your crops, and the ancestors will return, expelling the British and ushering in an era of unprecedented prosperity—resonated with a people desperate for hope. The resulting Xhosa Cattle Killing, a tragic blend of faith, desperation, and resistance, decimated the Xhosa nation and irrevocably altered its trajectory. This is the story of that tragedy, a deep dive into the complex historical, social, and psychological factors that converged to create one of the most heartbreaking episodes in colonial African history.

The Prophetess and the Prophecy: A Glimmer of Hope in a Time of Despair

The mid-19th century was a period of profound upheaval for the Xhosa. British expansion relentlessly encroached upon their ancestral lands, eroding their independence and disrupting their traditional way of life. Hamer v Sidway, while geographically distant, exemplifies the legal framework within which such colonial dispossession often operated. Adding to their woes, a devastating lung sickness decimated their cattle, the very heart of their economy, social structure, and spiritual life. It was into this atmosphere of escalating crisis that Nongqawuse, a young woman from near the Gxarha River, delivered her prophetic message in 1856.

Nongqawuse’s visions spoke directly to the Xhosa’s deepest anxieties and yearnings. She described a world where their revered ancestors would rise again, driving the British colonists into the sea. A new world would dawn, one of unimaginable abundance, with fields overflowing with crops and healthy cattle emerging from the earth. This potent message of hope, amplified by the desperation of the times, offered a seemingly miraculous solution to their plight. The price, however, was steep: the complete sacrifice of their remaining cattle, the very symbol of their wealth, status, and spiritual connection.

The Killing Begins: A Leap of Faith with Devastating Consequences

Why would a people destroy their own means of survival? Understanding the Xhosa Cattle Killing requires delving into the complex interplay of factors at play. British colonialism, with its attendant pressures of land dispossession and cultural disruption, created a climate of profound insecurity and resentment. The Turtle Bayou Resolutions, though arising from a different context, offer a glimpse into the type of resistance that can emerge against perceived oppression. Simultaneously, the lung sickness epidemic ravaged their herds, exacerbating their economic hardship and likely contributing to a sense of impending doom. Nongqawuse’s prophecy, offering a dramatic escape from this downward spiral, likely appeared to many as a radical but necessary act of faith.

The year 1856 marked a tragic turning point. Driven by a potent mix of faith, desperation, and perhaps a desire to resist colonial oppression, the Xhosa began slaughtering their cattle. It’s estimated that between 1856 and 1857, approximately 400,000 animals, the bedrock of their economy and culture were killed, along with the destruction of their crops. This act, intended to usher in a utopian future, instead plunged them into an abyss of unimaginable suffering. Some historians suggest that the cattle killing may have been a complex form of resistance, a final, desperate attempt to regain control in the face of overwhelming odds. Others posit that the prophecy exacerbated existing social and political tensions within the Xhosa community, contributing to the tragic outcome.

The Bitter Harvest: Famine, Social Collapse, and Colonial Exploitation

The promised utopia never materialized. The ancestors did not return, the British did not vanish, and the whirlwind brought not prosperity, but devastation. Instead, famine swept across the land, claiming the lives of tens of thousands of Xhosa, already weakened by hardship. The very act intended to liberate them became a tool of their further subjugation. Weakened and vulnerable, the Xhosa fell further under British control, their land and independence significantly diminished. Some historians argue that the British, though not directly responsible for the prophecy, probably exploited the ensuing chaos to consolidate their colonial ambitions.

The Legacy of Loss: Trauma, Interpretation, and Ongoing Research

The Xhosa Cattle Killing stands as a stark reminder of the complex interplay of faith, desperation, and the devastating consequences of colonialism. It compels us to consider the power of belief and the ways in which hope, when intertwined with desperation, can lead to unforeseen and catastrophic outcomes. It also underscores the enduring impact of colonial oppression and its role in shaping the destinies of colonized peoples. The echoes of this tragedy continue to resonate within the Xhosa community, a testament to the enduring power of this historical event and the complexities it presents.

The historical interpretation of Nongqawuse’s role remains a subject of ongoing debate. Was she a delusional figure, a victim of circumstance, or a cunning manipulator? The evidence suggests a more nuanced understanding is necessary. It’s likely that Nongqawuse, like many caught in the throes of crisis, genuinely believed in her visions. It’s also possible that her prophecies were influenced, either consciously or unconsciously, by the existing social and political tensions within the Xhosa community. Ongoing research continues to explore these complexities, seeking to understand the interplay of individual agency and historical forces that shaped this tragic event.

The psychological impact of the Cattle Killing on the Xhosa people was profound. The experience of famine, loss, and societal upheaval left deep scars on their collective psyche, shaping their subsequent history and cultural identity. The event continues to be a subject of reflection and remembrance, a testament to the enduring legacy of trauma and the resilience of the human spirit.

Why Cattle Were So Precious to the Xhosa

To fully grasp the magnitude of the sacrifice, it’s essential to understand the central role cattle played in Xhosa society. They were far more than mere livestock; they represented wealth, status, and a profound spiritual connection. Cattle served as a form of currency, were essential for dowry payments, and played a crucial role in religious ceremonies, acting as a link between the living and the spirit world. The lungsickness epidemic, which preceded the Cattle Killing, not only decimated their herds but also eroded the Xhosa’s economic stability, social structures, and spiritual well-being, making them particularly vulnerable to Nongqawuse’s message of hope.

The Xhosa Cattle Killing in the Broader Historical Context

The Xhosa Cattle Killing wasn’t an isolated incident. It unfolded within the larger context of colonial expansion, indigenous resistance, and millennialist movements around the globe. Comparing the event to other historical instances of millennialism reveals common threads: a belief in imminent transformative change, a charismatic leader offering a path to salvation, and a profound sense of crisis prompting a radical response. These comparisons offer valuable insights into the human condition and the complex ways in which people navigate periods of profound upheaval.

The Xhosa Cattle Killing remains a complex and tragic event, a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of colonialism, the power of belief in times of desperation, and the enduring legacy of trauma. Ongoing research continues to illuminate the nuances of this historical event, striving to provide a more complete understanding of its causes, consequences, and enduring significance. By exploring the multiple perspectives and complex factors at play, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the human cost of this tragedy and its lasting impact on the Xhosa people.